Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own Quotes—Wisdom on Writing and Life

Virginia Woolf was once asked to speak about women and fiction.

Woolf wandered the streets of London, sat by the riverside, pored over shelves full of books in the British Museum, went to luncheons, and considered the then state of literature. While working in a constricted space in that London where women weren’t even allowed to walk on turf paths in colleges (only men and students could), Virginia created a masterpiece on why there were limited women writers and even more limited writings by them.

Woolf delivered the lectures in October 1928 at the women’s colleges of Cambridge University. Published in September 1929, A Room of One’s Own is an essay based on those lectures.

Woolf went back to the works of Proust, Shakespeare, Emily Bronte, Jane Austen, Aphra Behn, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, Kipling, Keats, and many more known and unknown writers to understand the truth. She read fiction written by women and studied her contemporaries’ books. She contemplated why the writing of men scorned women and if women were writing good fiction.

In the essays, Virginia emphasized — while showing her detailed thought process — “that a woman needs money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.”

In addition to being a seminal work on feminism, A Room of One’s Own is an infinite pool of wisdom on writing and life. In the essay, Virginia Woolf argued passionately and statistically about how cultural, spiritual, and financial restrictions may limit our creative freedom.

Given the essay has so much to read into, I will only delve into the lessons on life and writing that Woolf was so benevolent in sharing with us.

I’ve drawn the starting line of this piece exactly where Woolf had started her own thought process. Right in the beginning, she objectifies her budding ideas on women and fiction, “Thought—to call it by a prouder name than it deserved—had let its line down into the stream. It swayed, minute after minute, hither and thither among the reflections and the weeds, letting the water lift it and sink it until—you know the little tug—the sudden conglomeration of an idea at the end of one’s line: and then the cautious hauling of it in, and the careful laying of it out?”

These sentences show how barely an idea sprouts up in a writer’s mind and how carefully it has to be explored. There’s so much one can create and so much one can miss.

Woolf adds, “Alas, laid on the grass how small, how insignificant this thought of mine looked; the sort of fish that a good fisherman puts back into the water so that it may grow fatter and be one day worth cooking and eating.”

If you are ever surprised to see a tiny thought shake and jiggle your mind, remember Woolf’s words— “But however small it was, it had, nevertheless, the mysterious property of its kind—put back into the mind, it became at once very exciting, and important; and as it darted and sank, and flashed hither and thither, set up such a wash and tumult of ideas that it was impossible to sit still.”

You have to give the thought the playground it deserves. The idea will deem you restless. And you shall be nothing, but glad. For an artist is always just a medium for the creation.

I gathered marvelous pearls of wisdom on writing and a writer’s thought process from the Room of One’s Own. So please don’t mind when I indulge a bit (too much).

A few pages down in the book, Virginia warns against changing the facts in fiction and forfeiting readers’ respect. “Fiction must stick to facts, and the truer the facts the better the fiction—so we are told. Therefore it was still autumn and the leaves were still yellow and falling, if anything, a little faster than before, because it was now evening (seven twenty-three to be precise) and a breeze (from the south-west to be exact) had risen.”

Her writing was so entangled with deep observations on human behavior and its inadequacies that I would have to switch between the two more often than I would like.

Reflecting on an unsatisfactory dinner, Adeline Virginia Stephen said, “The human frame being what it is, heart, body and brain all mixed together, and not contained in separate compartments as they will be no doubt in another million years, a good dinner is of great importance to good talk. One cannot think well, love well, sleep well, if one has not dined well.”

After a day of lunch, library, and dinner, Woolf suggests, “to think cleanly one must strain off what was personal and accidental in all these impressions and so reach the pure fluid, the essential oil of truth. For that visit to Oxbridge and the luncheon and the dinner had started a swarm of questions. Why did men drink wine and women water? What effect has poverty on fiction? What conditions are necessary for the creation of works of art?”

We have to set aside our grievances, disappointments, and worries to first ask the right questions. Only with the right queries can we land on the right answers.

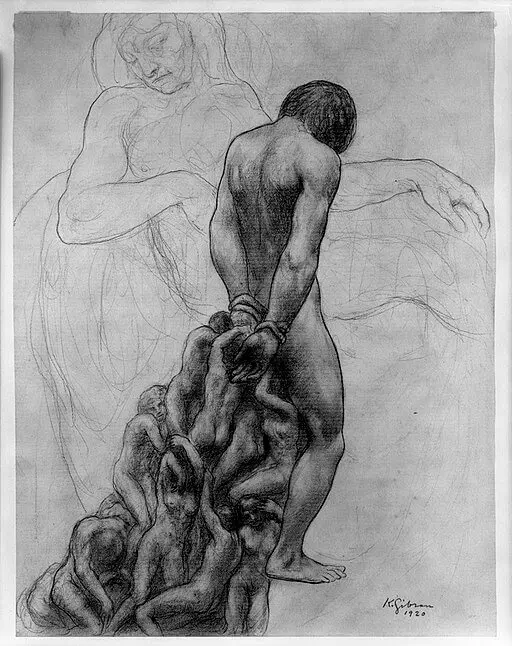

But observing the wide rift between men’s and women’s independence, Woolf herself became angry. In her anger, she drew a scowling picture of a fictional Professor von X who wrote the fictional The Mental, Moral, and physical inferiority of the female sex (she summarizes all that was written about the “inferiority of women” into one fictional item).

While commenting on her experience of drawing, she laid down an important truth about idleness, “Drawing pictures was an idle way of finishing an unprofitable morning’s work. Yet it is in our idleness, in our dreams, that the submerged truth sometimes comes to the top.”

Virginia had an immense talent (that she never ceased sharpening) to look beyond what was shown and find the truth on her own. I will try to share here as many of her tips on critical understanding as I can (along with many of Virginia Woolf A Room of One’s Own quotes).

After reading the newspaper at lunch, the writer set aside her anger and calmly observed, “When an arguer argues dispassionately he thinks only of the argument; and the reader cannot help thinking of the argument too. If he had written dispassionately about women, had used indisputable proofs to establish his argument and had shown no trace of wishing that the result should be one thing rather than another, one would not have been angry either. One would have accepted the fact, as one accepts the fact that a pea is green or a canary yellow.”

Woolf concluded she was angry because he (the editor of the newspaper and other patriarchal supporters and men writers) was angry. But she couldn’t understand the anger.

She further observed, “Yet it seemed absurd, I thought, turning over the evening paper, that a man with all this power should be angry. Or is anger, I wondered, somehow, the familiar, the attendant sprite on power?”

To observe anger, the writer cut open the bare truths of human life like one’s body is split open in a surgery,

“Life for both sexes—and I looked at them, shouldering their way along the pavement—is arduous, difficult, a perpetual struggle. It calls for gigantic courage and strength.” (And some right ideas for self improvement – the things we should care for to lead a good life.)

She argues that we all need to be confident to live, else we would be nothing more than babies in a cradle. And most of us gain confidence by thinking of others as inferior to us.

“By feeling that one has some innate superiority—it may be wealth, or rank, a straight nose—for there is no end to the pathetic devices of the human imagination—over other people.”

“That is why Napoleon and Mussolini both insist so emphatically upon the inferiority of women, for if they were not inferior, they would cease to enlarge.”

We all are lying to ourselves if we take mindless criticism as anything else than an effort by the harbinger to feel better about himself. But the people who appear terrible because of their shameless opinions also have a lot to deal with. (This piece on emotional intelligence and understanding our emotions may help further.)

Woolf talks about how the patriarchs and the professors also had endless difficulties and terrible drawbacks to contend themselves with. “Their education had been in some ways as faulty as my own. It had bred in them defects as great. True, they had money and power, but only at the cost of harboring in their breasts an eagle, a vulture, forever tearing the liver out and plucking at the lungs—the instinct for possession, the rage for acquisition which drives them to desire other people’s fields and goods perpetually; to make frontiers and flags; battleships and poison gas; to offer up their own lives and their children’s lives.”

After observing others’ drawbacks and limitations, the writers’ fear and bitterness transformed into pity and toleration and later the pity and toleration dissolved to give way to freedom to think of things in themselves.

“A writer’s greatest power could be to think of things in themselves” — objective criticism devoid of personal fury is the only valuable criticism.

“She may be beginning to use writing as an art, not as a method of self-expression.” — Virginia Woolf

I didn’t have to look too carefully for lessons on life for the writer has sprinkled the text with important questions, “Is it better to be a coal-heaver or a nursemaid; is the charwoman who has brought up eight children of less value to the world than, the barrister who has made a hundred thousand pounds?”

— these questions reminded me of the Little Prince who warned us against the demerits of assessing every act and thought rather than just being.

While discussing why women didn’t write exceptional fiction in Elizabethan time, Woolf put light on some of the important aspects of fiction writing,

“For fiction, imaginative work that is, is not dropped like a pebble upon the ground, as science may be; fiction is like a spider’s web, attached ever so lightly perhaps, but still attached to life at all four corners. Often the attachment is scarcely perceptible; Shakespeare’s plays, for instance, seem to hang there complete by themselves. But when the web is pulled askew, hooked up at the edge, torn in the middle, one remembers that these webs are not spun in mid-air by incorporeal creatures, but are the work of suffering human beings, and are attached to grossly material things, like health and money and the houses we live in.”

Combining the difficult and restricted condition of women’s life and writing, Virginia concludes, “That woman, then, who was born with a gift of poetry in the sixteenth century, was an unhappy woman, a woman at strife against herself. All the conditions of her life, all her own instincts, were hostile to the state of mind which is needed to set free whatever is in the brain.”

Woolf doesn’t take much time to ask the seminal question, “But what is the state of mind that is most propitious to the act of creation?”

She has touched upon a chord that strings too close to my heart. Woolf writes, “the indifference of the world towards Keats and Flaubert and other men of genius that was so hard to bear turned from indifference to hostility in women. The world did not say to her as it said to them, Write if you choose; it makes no difference to me. The world said with a guffaw, Write? What’s the good of you writing?”

Men of known distinctions were found to make comments such as “the best woman was intellectually the inferior of the worst man” and “a woman’s composing is like a dog’s walking on his hind legs.”

How shall we measure the effect of discouragement upon the mind of the artist? Virginia was sure that hateful and negative comments must have demotivated any girl and affected her work profoundly.

“There would always have been that assertion—you cannot do this, you are incapable of doing that—to protest against, to overcome. Her mind must have been strained and her vitality lowered by the need of opposing this, of disproving that.”

I write for a living. But while I shifted my focus from engineering work to writing, many times I was told that a job is better than any creative work. I, naturally, have been expected to run a family, cook chapatis for my husband (for he might be hungry just eating rice), keep fasts, and reject every profession that my in-laws might not approve of. I, naturally, opposed this and disapproved of that.

But the rebellion has come at a cost. I’ve found myself operating with low energy many times. Under the weight of my need to constantly assert that I will have an autonomous career, I’ve seen myself overburdened with anxious thoughts rather than focusing on my art.

I’m not alone in feeling overwhelmed by the opinion of others.

Virginia Woolf confirms, “Among your grandmothers and great-grandmothers there were many that wept their eyes out. Florence Nightingale shrieked aloud in her agony. Moreover, it is all very well for you, who have got yourselves to college and enjoy sitting-rooms—or is it only bed-sitting-rooms?—of your own to say that genius should disregard such opinions; that genius should be above caring what is said of it. Unfortunately, it is precisely the men or women of genius who mind most what is said of them.”(And I’m a mere mortal.)

Woolf asks, “Remember Keats. Remember the words he had cut on his tombstone. Think of Tennyson; think but I need hardly multiply instances of the undeniable, if very fortunate, fact that it is the nature of the artist to mind excessively what is said about him.”

“Literature is strewn with the wreckage of men who have minded beyond reason the opinions of others.” — Virginia Woolf

Now Virginia answers her own question — what state of mind is most propitious for creative work — “the mind of an artist, in order to achieve the prodigious effort of freeing whole and entire the work that is in him, must be incandescent, like Shakespeare’s mind. There must be no obstacle in it, no foreign matter unconsumed.”

Virginia said of the creative mind, “Consume all impediments and become incandescent.”

“All desire to protest, to preach, to proclaim an injury, to pay off a score, to make the world the witness of some hardship or grievance was fired out of him and consumed. Therefore his poetry flows from him free and unimpeded. If ever a human being got his work expressed completely, it was Shakespeare. If ever a mind was incandescent, unimpeded, I thought, turning again to the bookcase, it was Shakespeare’s mind.”

I used to think that one’s impediments will allow a person to write or create better. The creator would express her anguish in her writing or music or poetry.

Maybe it is not so much of the anguish we need to see but the depth reached by that anguish. For we are all looking for answers to our own pain, anger, disappointment, and hurt.

Woolf dived deep to see if women’s writing was affected or harmed by their circumstances, and if so, how.

She said about Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, “Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. That was how Shakespeare wrote, I thought, looking at Antony And Cleopatra and when people compare Shakespeare and Jane Austen, they may mean that the minds of both had consumed all impediments; and for that reason we do not know Jane Austen and we do not know Shakespeare, and for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word that she wrote, and so does Shakespeare.”

But about Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre, Woolf said she could notice the jerk in the writing, the indignation was visible.

“One sees that she(Charlotte Brontë) will never get her genius expressed whole and entire. Her books will be deformed and twisted. She will write in a rage where she(Jane Austen) should write calmly. She will write foolishly where she should write wisely. She will write of herself where she should write of her characters. She is at war with her lot.”

If we stay at war, we will not only harm ourselves but will spoil any creative work we produce. We — not just writers but creators of all kinds and as human beings whose lives depend on how we think— should pass through all obstructions as ghosts and continue to write our own stories.

“Your entire devotion is due to your story. You cannot leave it to attend to some personal grievance. Let not anger tug at our imagination or devotion and deflect it from its path.” — Virginia Woolf

I believe my inspiration to write even if you are bleeding will push you ahead on a rough journey.

What are novels and novel writing for Virginia Woolf?

“It is the writer’s job to collect reality and communicate it to the rest of us,” Woolf says.

“If one shuts one’s eyes and thinks of the novel as a whole, it would seem to be a creation owning a certain looking-glass likeness to life, though of course with simplifications and distortions innumerable.” — Virginia Woolf

Why is the integrity of the novelist important?

This might be the most important lesson for a writer — “What one means by integrity, in the case of the novelist, is the conviction that he gives one that this is the truth. Yes, one feels, I should never have thought that this could be so; I have never known people behaving like that. But you have convinced me that so it is, so it happens.”

“Or perhaps it is rather that Nature, in her most irrational mood, has traced in invisible ink on the walls of the mind a premonition which these great artists confirm; a sketch which only needs to be held to the fire of genius to become visible. When one so exposes it and sees it come to life one exclaims in rapture, But this is what I have always felt and known and desired! And one boils over with excitement, and, shutting the book even with a kind of reverence as if it were something very precious, a stand-by to return to as long as one lives, one puts it back on the shelf, I said, taking War and Peace and putting it back in its place.”

None of us have to write brilliant stories. We have to write true stories. The writer is free to choose the truth. But she needs to convince her readers that that is the truth. (Also read my 27 writing tips for new writers to write better.)

Woolf comments on bad writing, “If, on the other hand, these poor sentences that one takes and tests rouse first a quick and eager response with their bright coloring and their dashing gestures but there they stop: something seems to check them in their development: or if they bring to light only a faint scribble in that corner and a blot over there, and nothing appears whole and entire, then one heaves a sigh of disappointment and says. Another failure. This novel has come to grief somewhere.”

While writing your truth, ask yourself a few questions,

“Is your mind pulled from the straight, and made to alter its clear vision in deference to external authority?”

“Is the writer saying this by way of aggression, or that by way of conciliation?” “She was admitting that she was ‘only a woman’, or protesting that she was ‘as good as a man’”?

Or is she running purely on her reason? “For if you think of something other than the thing itself, there’s a flaw.”

“So long as you write what you wish to write, that is all that matters.” — Virginia Woolf

If you catch someone else’s voice in your head critiquing you or grumbling or dominating or shocked or grieving — listen to it again. If the voice is not yours, shut it off.

While critiquing a book Woolf said (and we can learn a lot about the method of reviewing one’s writing here), “The smooth gliding of sentence after sentence was interrupted. Something tore, something scratched; a single word here and there flashed its torch in my eyes. She was ‘unhanding’ herself as they say in the old plays. She is like a person striking a match that will not light, I thought. For while Jane Austen breaks from melody to melody as Mozart from song to song, to read this writing was like being out at sea in an open boat. Up one went, down one sank. This terseness, this short-windedness, might mean that she was afraid of something; afraid of being called ‘sentimental’ perhaps; or she remembers that women’s writing has been called flowery and so provides a superfluity of thorns.”

Spreading more vibrant rainbows of writing over the deep blue sky, Virginia says, “a writer can break the sequence of sentences or scenes as long as they are doing that for the sake of creating and not for the sake of breaking (perhaps to prove a point).”

And how do we add new content to a longer piece of ongoing work?

“And she reaches out for it, I thought, again raising my eyes from the page, and has to devise some entirely new combination of her resources, so highly developed for other purposes, so as to absorb the new into the old without disturbing the infinitely intricate and elaborate balance of the whole.”

Virginia Woolf also warns against writing in the spirit of scorn and ridicule saying the results of that spirit would be futile.

A few more moons of wisdom on the art of writing straight from the heart of Virginia Woolf,

“Be truthful, one would say, and the result is bound to be amazingly interesting.” — VW

“She wrote as a woman, but as a woman who has forgotten that she is a woman, so that her pages were full of that curious sexual quality which comes only when sex is unconscious of itself.” — VW

“Do not skim the surfaces. But summon, beckon, and get together to look beneath the surfaces. Without doing anything violent, show the meaning of all this.” — VW

“After reading on good writing, one should feel as if one had gone to the top of the world and seen it laid out very majestically beneath.” — VW

“The only sort of writing of which one can say that it has the secret of perpetual life is the one that explodes and gives birth to all kinds of other ideas.” — VW

“It is fatal for anyone who writes to think of their sex.” — VW

And I conclude this meditation by sharing what Virginia Woolf had said at the beginning of the essay, “Lies will flow from my lips, but there may perhaps be some truth mixed up with them; it is for you to seek out this truth and to decide whether any part of it is worth keeping. If not, you will of course throw the whole of it into the waste-paper basket and forget all about it.”

You can decide how much, if any at all, you want to keep of this.

Browse more books of Virginia Woolf here and find A Room of One’s Own here.

Did you enjoy these lessons on writing and life? Which one of these quotes from Virginia Woolf A Room of One’s Own is your favorite?

*****

My much-awaited travel memoir

Journeys Beyond and Within…

is here!

In my usual self-deprecating, vivid narrative style (that you love so much, ahem), I have put out my most unusual and challenging adventures. Embarrassingly honest, witty, and introspective, the book will entertain you if not also inspire you to travel, rediscover home, and leap over the boundaries.

Grab your copy now!

Ebook, paperback, and hardcase available on Amazon worldwide. Make some ice tea and get reading 🙂

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter "Looking Inwards"!