Letters From Van Gogh

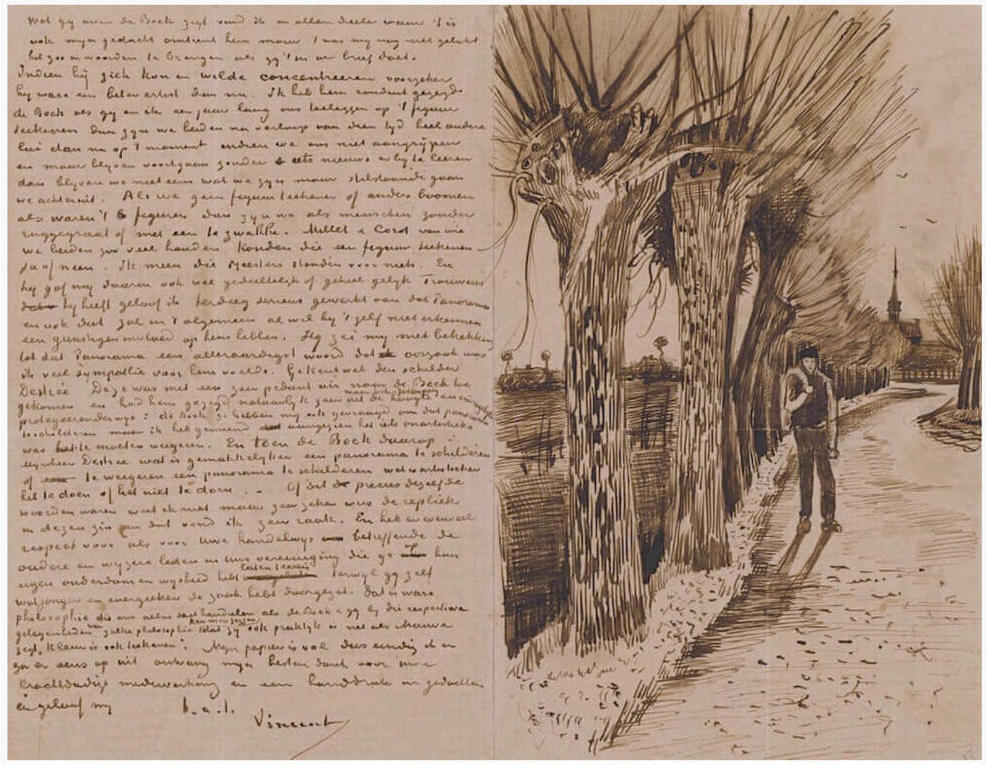

The celebrated painter Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) regularly wrote to his brother Theo, his ardent supporter and friend.

Out of the hundreds of letters by Vincent van Gogh, the Vincent van Gogh organization has put about hundred on their website. The book Ever Yours: The Essential Letters contains a broad selection of 265 from a total of 820 letters in existence. All letters are poetic, sincere, and full of intelligent advice on pursuing one’s profession. But out of all letters of Van Gogh to Theo, a letter dated 15 October 1881 left me no choice but to write this piece on hardships of work and the courage to pursue any skill.

Courtesy: www.VincentVanGogh.org

(Another piece on learning to practice anything and becoming a master: inspired by Vincent van Gogh letters. Coming soon.)

How Vincent Navigated the Art of Painting and Its hardships: As Written in the the letter of Vincent van Gogh to Theo

Vincent van Gogh made most of his paintings — almost 2000 — in his last two years 1889 and 1890. He wasn’t recognized for his artwork during his lifetime. Vincent was poor and was supported by his brother (mostly), father, and other friends. Records can only confirm the sale of one of his paintings when he was alive.

Vincent not only needed paint, canvases, brushes, paper, and chalk every day but also needed boundless patience to slowly persevere. Though every letter of Van Gogh is a glowing cosmic of self-reflection, determination, and endurance from which you can absorb infinite stars of wisdom, in this letter Vincent writes to his brother about the hardships of a professional and why he decided to stick it out as a painter and artist despite the difficulties.

While acknowledging the favorable comments of his brother on his paintings, Vincent underlines the resistance of nature towards an artist. His comments can be understood in light of any work: nature represents the environment in which the labor withstands and all crafts need practice.

“Nature always begins by resisting the draughtsman, but he who truly takes it seriously doesn’t let himself be deterred by that resistance, on the contrary, it’s one more stimulus to go on fighting, and at bottom nature and an honest draughtsman see eye to eye.

Nature is most certainly ‘intangible’ though, yet one must seize it, and with a firm hand. And now, after spending some time wrestling and struggling with nature, it’s starting to become a bit more yielding and submissive, not that I’m there yet, no one is less inclined to think so than I, but things are beginning to go more smoothly. The struggle with nature sometimes resembles what Shakespeare calls ‘Taming the shrew’ (i.e. to conquer the opposition through perseverance, willy-nilly).”

Vincent van Gogh

![Van Gogh on Delving Deeply, Hardships, and Doing [In a Letter to Theo] 2 512px Vangogh femme dans un jardin a woman working in the garden one of van goghs](https://www.onmycanvas.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/512px-Vangogh_femme-dans-un-jardin-a-woman-working-in-the-garden-one-of-van-goghs.jpeg)

One may always surrender the task and say, “this is too hard, I can’t do it.” (Or get tired of work.)

But Vincent — an artist who in his mentally tumultuous times could project the hardly conceivable flows of turbulences into his paintings — says, “In many things, but more particularly in drawing, I think that delving deeply into something is better than letting it go.”

The importance of focusing on the one thing at hand, be it writing a paragraph, painting a tree, selling a business idea, or writing a line of code is explained by Vincent in compassionate words.

“If one draws a pollard willow as though it were a living being, which it actually is, then the surroundings follow more or less naturally, if only one has focused all one’s attention on that one tree and hasn’t rested until there was some life in it.”

Vincent van Gogh

A painter isn’t the only one who puts life in trees on canvases. Be it a shirt a tailor stitches, a path a gardener rakes, a sonata a musician practices, a baguette a baker kneads — all of these become alive when their creator gives all of their attention to it.

Everything that is great is so because its creator didn't rest until she gave the work her best

We all become doubtful when we spend a lot of time learning (Rainer Maria Rilke shares great wisdom on doubts.). Our results aren’t yet visible to us, let alone to the world. Hastening, we wriggle out of the motherly arms of learning and run towards the tower of results.

But for those times Van Gogh has promising advice as he shares with one friend De Bock,

“De Bock, if you and I were to concentrate on figure drawing for a whole year, afterwards we’d both be completely different people from what we are now; if we fail to get a grip on ourselves and simply go on without learning anything new, we won’t even remain what we are but, standing still, we’ll go backwards.”

Vincent van Gogh

We also either become lazy or hesitant while taking upon new work. When I have to write a second-person narrative or tackle a new topic, I’m unsure. Would I be able to handle the writing? Is the effort to learn worth the results?

![Van Gogh on Delving Deeply, Hardships, and Doing [In a Letter to Theo] 3 512px Vincent van Gogh Wheatfield under thunderclouds Google Art Project](https://www.onmycanvas.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/512px-Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Wheatfield_under_thunderclouds_-_Google_Art_Project.jpeg)

Even though Vincent was still learning and didn’t think of himself as the master, or any good at all, he always looked up to the masters and drew inspiration from them.

“Millet and Corot, whom we both like so much, could they paint a figure or couldn’t they? I mean, those Masters balked at nothing.” Vincent asked another contemporary artist friend.

If we have to master any profession or art, we have to be courageous to take up just about anything. Otherwise, our days would be counted for what we didn’t do.

At times we wonder whether the work is worthy of doing. For such times Vincent has a beautiful and real example (of which Van Gogh letters are full) of a conversation between a friend De Bock and a painter Destrée.

“Surely you know the painter Destrée. He had gone up to De Bock with a very pedantic air and had said to him, very superciliously, of course, and yet in a mealy-mouthed and unbearably patronizing way: De Bock, they also asked me to paint that panorama but I thought, since it was so unartistic, that I had to refuse. To which De Bock replied: My dear Mr Destrée, what is easier, painting a panorama or refusing to paint a panorama?

What is more artistic, doing it or not doing it?” Vincent van Gogh asked.

To conclude,

I could lay down the pen you can pause on your path labor can be given up by men we all quit the works of wrath but what then we are a pale blue dot in the cosmic one's work define who they are without the labor only comes despair the wine floweth but what am I known for give me a pen you please walk we toil, friend for only agony leads to delight we are a pale blue dot in the cosmic one's work define who they are

Have you read the Letters by Vincent van Gogh? Do you think doing is better than not doing? Why?

Images Courtesy: Vincent van Gogh, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter "Looking Inwards"!

![Van Gogh on Delving Deeply, Hardships, and Doing [In a Letter to Theo] 1 Vincent_van_Gogh Self-Portrait for vincent van gogh letter to theo on courage-perseverance-artists-life small.jpeg](https://www.onmycanvas.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Vincent_van_Gogh_-_Self-Portrait-for-vincent-van-gogh-letter-to-theo-on-courage-perseverance-artists-life-small.jpeg)