36 Months as an Itinerant Writer: What It Means to Live On The Go

Table of Content [TOC]

- Introduction

- How Do We Find Homes Around India—3 Years Without an Apartment

- How do we make ourselves at home in such transience?

- Working on the Go

- How do we manage food on the go?

- How do we pack?

- Coming to the money part.

- How do I earn on the go?

- How do we ensure low footprints?

- Reflecting on the Journey

- A Fairy Tale

- After 36 months of Hotels, Hostels, and Guesthouses, Do I Miss Home?

- Why did we do it? Why did we leave home?

- Many people ask me how did our families react to this life.

- Scooby dooby doo, where are you?

- Homeless for 3 Years, Or, With a Home Everywhere?

- What have I learned from all this?

- What is the one takeaway from the journey?

- What is the one thing that has helped us the most?

- What is the one thing we never take for granted?

- What is the one thing I could have done without?

- What’s next?

- Would I ever want a home of my own?

Introduction

January 5′ 2024 Bangalore

Here I’m in a hotel in Bangalore, writing this narrative and wondering why I feel so cold and why am I so uninterested and unenthusiastic about everything. I have stayed in hotel rooms before for weeks. Not often do I feel this gloomy, directionless, and filled with the notion that nothing is going anywhere.

Is my sadness associated with the fact that all my friends in the city are busy with their kids and office? Either they are planning a vacation two to three months down the line, wondering how they would manage with their children, or they have returned from a holiday, coping with the consequences. Their kids aren’t well, office work feels worse than before, and the paraphernalia of city life has been at their throats since they arrived.

Or am I so dejected because—as my friend Jitaditya from the amazing offbeat travel blog Travelling Slacker says—Bengaluru, this busy city of software giants and startups, makes a person lethargic and uninterested? Maybe the gloomy and grey weather has dampened my enthusiasm as well. The sun came out for a few minutes. I was hot immediately, and now it is cold and windy again. The climate is dreary, at best. The constant traffic outside my hotel window could have also caused my despondence. Infantry Road, home to foot soldiers of the colonial British power in the 19th century, has an incessant movement of vehicles from early morning to, well, next early morning. Despite the window glass, you constantly hear the honks and vrooms.

My hopelessness may have something to do with the pending work on the blog as well. For the past two years, I was occupied with a creative writing project that didn’t let me look up from it. Concomitantly, the blog has suffered.

Perhaps, this feeling of transience and non-belonging I get upon seeing families, including every friend, doing the usual things everyone of my age does is irking me. Children, jobs, house, school, parents, workers, apartment events, et cetera.

I don’t have any of it. I mean I do have family, a partner, parents, a car, and my never-ending work. But while my friends and acquaintances are comfortably, let’s just say, settled in flats and houses with multiple workers to help them, I live from guesthouse to guesthouse, sometimes, just because they will have me. I don’t have many employees, but an ever-changing staff around India keeps my room clean, cooks for me at times, and runs the online portals that ensure a roof above my head.

Is it the lack of a sense of belonging, my transitory presence in every place, the wandering life—tomorrow I have to leave again—that is bothering me?

My partner and I left our tiny rooftop abode in Bangalore (Karnataka) on 31st January 2021, packed our things in our car, and got onto the road. This blog post details the beginning of our trip and how and why we made our way through India during the second wave of COVID-19.

Now after three years in short-term accommodations, how do I feel about all this living from day to day, and what are the lessons I have learned?

As a reader recently told me on Twitter, “It’s really hard to pull off this lifestyle.” I agree with him.

Some mornings when I wake up, I can’t tell where I am.

But it is easy, and it is hard, and I will have to go into details to explain what I mean.

How Do We Find Homes Around India—3 Years Without an Apartment

How do you find these places? How do you find accommodations?

That is the first question everyone who hears our story asks.

Finding hotels and homestays—or sometimes a tree hut, a stilt house, wooden cabin, jungle mud cottage, beach home, a tent, a ship, a 3400-m high government guesthouse in the wilderness, an apartment, mountain home, a friend’s house—a decent roof above our head—has been the hardest part of our journey.

There have been nights when I have felt we will not find a place (like yesterday, Feb 10′ 2024, in Thrissur, Kerala): everything is sold out, accommodations don’t appear good, and prices are beyond our budget.

Despite the tariffs, the quality of the accommodation and services promised can’t be guaranteed ever. Even the simplest things: regular cleaning, hot water from the geyser, and the internet are issues in some places. Sometimes even requests such as not having cockroaches in corners or rats invading at night, a refill of the gas cylinder as promised, and linen change are considered outrageous.

I have spoken a lot about Indian hotels/accommodations and Indian homestays in the linked articles. To add, I can say that our hospitality industry is unstructured. Even people who have not traveled can put up a home on rent or Airbnb. Amongst so many different cultures, the living style and rules of homes change from village to village. We are expected to follow them all. As most of us do, some hosts overvalue their property, and tariffs are high. Things have worsened after COVID-19. But whether the place and the service justify the cost is debatable. Hotel staff is underpaid, there are no regularized standards, and again, most people working in the tourism industry are untrained, haven’t traveled as much, and don’t personally care about the guest experience. Our hospitality staff is often overworked, so leave friendliness and personal care, even professionalism is a commodity you rarely find.

The elephant in the room here is that travel in India—traditionally—is associated with short vacations on which people relax, drink, eat, and have fun.

How many of us take an overnight bus to an unknown town, pay to a dusty hotel, and eat strange food to learn about that place?

I didn’t.

Before I traveled to Southeast Asia and South America in 2016, I looked at traveling as a vacation. But having quit my job, I headed off to Southeast Asia without a return ticket or a plan on my mind. I wanted to impress my friends and ex-colleagues. “I will travel solo for an indefinite period,” I said. At that time, the idea of purposeful, slow travel was as thinly spread as “No dinner is a healthy lifestyle.”

Though some of my reasons for traveling were wrong, my method was (sort of) right from the beginning. My heart was in the right place, too. In Thailand, I followed the advice of a couple of popular travel blogs. Soon I was trusting my instinct. By mistake, I overstayed my visa in Thailand, paid a fine, and arrived in Cambodia by a cross-border train at night. Luckily, the train had three other international travelers too. We got a taxi to the nearest town. I didn’t have anything booked, so I tagged along with a traveler from Chile to a cheap hostel she had reserved. In Vietnam, I arrived in most places without a reservation. Things worked out in the end, and I never slept on the road.

The magical thing that happens when you travel slowly—without an end date in mind—is that you take your time. You don’t have to rush anywhere after breakfast, so you sit and watch the chicken rice hawker play with her child. You connect with crazy people from around the world who had the same crazy idea as you—we will pack our bags, book a ticket, and go to this unheard-of place. The harder it is to get there, the more you want to go. You stare at the tri-rickshaws, eat in malls, and befriend people you end up hating. You climb waterfalls, wander around historical places as sad as human torture centers and killing grounds, and jump in the water because everyone does.

I did all of it. At some juncture, I started seeing the point in slow, observant travel in which one is not rushing from one destination to another or isn’t lying down in the hammock all the time, sipping coconut shakes. I have nothing against coconut shakes. But in Southeast Asia and on my nine-month travel in South America, I came across tourists who immersed in the culture, had adventures slowly, and for whom travel was a method of discovery. I became friends with Canadians, Chileans, Chinese, French, Dutch, British, North Americans, and Germans who traveled with their life savings to explore, learn, and undo.

I wanted to see the world, too.

South America changed me is a huge understatement.

Everyone, at least once, should leave their home for a year, go to a distant culture whose language they do not know, and live in it. If by the end of the stay, you aren’t transformed, maybe you didn’t let go.

This guide on South America has everything you need to know.

Now, travel has become a form of living for me. I travel, I live, I write. I can turn these phrases around in any order, but they all mean the same to me.

Given that long-term travel—ours would be called indefinite travel, as we don’t have an end date—isn’t common in India, most hosts, staff, and owners do not understand why we are staying for more than a couple of days. Or why having a work set up in a room: a simple straight chair and table could be important. Or why one might want to skip the heavy breakfast (to start the day light and eat a bit later). They don’t appreciate the need for a kettle, a larger space, regular cleaning, and a quiet atmosphere. I wouldn’t even go as far as asking for two workstations, laundry service, and some plates and spoons in the room for one to have fruits.

It is how it is. We get what we get. Then we make do.

Apart from what I have written on my Travel Resources page, this accommodation guidebook, and the homestay manual, I can say that we do not find places, they find us. Most often, things work out the way we wouldn’t have imagined them.

We book online sometimes (not Airbnb: read My Travel Resources to know why), zoom into Google Maps and call, leave a question on a contactless property, look through accommodation portals of communities, follow friends’ recommendations, check out nearby properties of a present stay, extend our reservation and negotiate for a long-term price, and—one of our best methods—drive through the place, look at guesthouses from outside to notice any red alerts, request to show, and unpack.

The best way to go is to tell the intended duration of stay, ask about drinking water, mobile network, and wifi connection, express you would like a quiet stay, choose a place that isn’t crowded by other guest rooms (if possible), and enquire about cleaning schedules.

After doing this for three years, I don’t take even the basics for granted any more.

Negotiations aren’t easy, they aren’t hard. Slowly, we are getting to know how much one should pay, where to stop bargaining, and what to expect. From rooms and homes for three hundred rupees per night to ten thousand per night, we have stayed in them all.

We have learned that more money doesn’t mean better cleaning, cordial staff, bigger space, or quick resolution of system failures. In fact, we have gotten better care in smaller and more affordable spaces. A Pondicherry homestay that cost us less than a thousand rupees per night and provided breakfast and a washing machine is a family I can return to anytime.

Setting expectations right from the beginning is the only way to go. When we are shy about something or book the place even though the host has already screamed at us, things don’t turn out so well.

Never pay the whole amount in the beginning. Try to get a system established since day one.

Mostly, the system fails. Be okay with that.

Upon check-in, an hour might go in coordinating with the staff to clean, get the towels, toilet paper, water, and a usable kettle, and so on. In a majority of our stays in the past three years, even at family-run homes or in expensive resorts, we have, unfortunately, found the place dirty, unchanged bedsheets that still stank of smoke from the previous guest (happened recently in Mysore), giant cockroaches in bed (in Sikkim), filth or alcohol bottles under the bed and around the living area (recently in Bangalore), unusable bathroom (twice not even flushed), dysfunctional geysers from which water fell off the wall, hair-wrapped soaps, and so on. The utensils and induction were in the pictures but not in the property.

Having the house maintained regularly over a long stay is another headache. Sometimes, the staff is persistent on daily tips: even when they have not done a good job, and we stayed for six months.

On some days, you are bound to be miserable. You have been asking for housekeeping because you wanted the chore done and because of hairs on the floor, overflowing dustbins, and wet towels. When the staff comes hours later after multiple reminders, you aren’t happy. You can’t care anymore. But you still see the footmarks and the dead lizard and the foot-mat that is black now, but they are not changing it.

You request them. You feel powerless. One of the housekeeping looks at you with such hostility in her eyes and such a sullen face that you are sure she hates you. She hates her job though, not you. When you direct them, trying to make the room your home, you face resistance. They talk to you or amongst each other in a language you don’t understand. Then they laugh.

In a hotel in Kerala, I requested a wet mop over footprints, and the housekeeping lady moped. Then she looked at me and gave out a contemptuous cry—even though we had just been laughing together.

I felt judged. I felt horrible. I might have cried a little bit too.

This is the back-and-forth I dread, the thing that makes me hopeless on some otherwise sunny afternoons. Going into the details—please provide fresh glasses and please put some cleaner in the toilet—makes me guilty.

Over time, instead of depending on external friendliness, I have started to believe nothing I am asking is so outrageous that another human wouldn’t have asked for it. That people are complex. Each day is different, and the love, cordiality, and efficiency of the staff and hosts would change from day to day.

If a place gives you too much headache, get out. Nothing is worth a headache. You will find another home, but the most important is to be at peace.

Sometimes, I prefer not to have any services during my stay. Then we do as we like.

At some homes or hotels where we stayed longer than a normal traveler, we felt uninvited, or as my partner says, “We overstayed our welcome.” That we should have left a bit ago. What makes us think that? A certain comment, dour looks from the family or the workers, or a sudden retraction of services and isolation from the hosts.

Sometimes, the staff of a remote inn is surprised to see us stay beyond the weekend, working in the room. In a hotel on the outskirts of Mysore (Karnataka), we left our room for lunch and handed the key to the staff to clean. When we returned, the hotel was locked from inside. For the past few days, we had been wandering around the migratory bird colonies on the Kaveri River tributaries. Now, it was time to work. The Kannada-speaking caretaker woke up from his afternoon sleep, opened the door while rubbing his eyes, and asked: “You’re not going to the site?” He meant we were not going sightseeing. Our room wasn’t clean. We worked in the corridor while it was being done up by a begrudging staff who did a rough job.

That afternoon, I was sure the staff didn’t appreciate our presence in the hotel at that time of the day.

We might be a trouble to the workers who are used to guests leaving every morning and returning at night after seeing the attractions of the destination. We stay and request replenishment for water, toilet paper, and tea bags and call if the power or internet goes off. Sometimes, the forbidding look of the boy who brings us supplies or of the housekeeping gives it away.

In India, the service employees are paid peanuts. We tip frequently: from a hundred rupees to even five hundred. But that still doesn’t make it. The hardships of the job raise the frowns back up again, and we are left to wonder if we have been nice enough or if we are pettifogging.

Then, I can’t do anything more than ignore the expressions and tell myself, as my partner says, that we can never know what a person is going through, can never assess their inner turmoils by their face, and it is not as much about us as we think.

Things are neither black nor white.

On days, we just miss friendliness. Even when we have been in a hotel for a week, and probably want to stay for longer, we don’t feel welcomed.

Even in our own homes, no one welcomes us back every day. Perhaps someone might. But it is home, after all. We cook, sleep, and invite guests over whenever we like. We have friends in the city. In a temporary stay, you feel out of place, and a little bit of friendliness and simple gestures put you at home right away.

At times, we have resided in accommodations for months without feeling that homeliness outside the boundaries of our room, apartment, or hut. We still stay put. That was the need of the hour. Either we had to be in that locality, and there was no other better place, or we had already paid, or we were too tired to notice the indifference and so made do. The home was, in itself, sufficient enough for that time even with its imperfections and particularities. And when in one Pondicherry home we couldn’t take the host’s inappropriate and unjustified demands, we involved the police and left immediately.

Overall, in three years, we have stayed in places from half an hour (the place was filthy, so we left and asked for a refund) to six months. On average, my partner and I have spent INR 30,000 per month on rent including electricity, internet, water, drinking water, gas, linen and towel change, parking, and cleaning services. Sometimes, the rent even covered tea, coffee, local fruits and vegetables, dinners and breakfasts, and fridge et cetera. We have zero maintenance costs. No carpet cleaning, painting, or plumbing charges. No headache.

Our cab or taxi expenses are nill because either we drive or use public transport: buses, metro, or simple modes such as autos and tri-rickshaws. Mostly, we walk. We cycle. Only in one few-months-long stay, we had costs of moped, bicycles, electric bikes, and a scooter that I believe would be covered by this average monthly rent.

The past three months have been a bit more expensive. Our locations have been Chandigarh, Jaipur, Ranthambore National Park, Satpura National Park, Bhopal, Nagpur, hotels on the highway, Goa, Bangalore, Mysore, and Kerala. But I am sure this cost would be averaged out by other cheaper accommodations, monthly rentals, or family stays over the next few months.

Our methods and needs are forever evolving.

Once upon a time, I used to book the cheapest place for myself. Then, to comfort my partner, we reserved accommodations more spacious and presentable, and that promised a minimum comfort. I applied filters such as wifi and parking (or at least an approachable road) and prioritized cleanliness. Now, instead of one room, we look forward to bigger spaces, apartments, and larger hotel rooms. We even got two rooms a couple of times in Himachal when each was four hundred rupees per night only. As our living space doubles as a workspace—and almost every other utility space—a larger accommodation keeps us from running into each other all the time. Later, we get into budget guest homes and average the costs.

And as someone who used to choose homestays over other accommodations, now we prefer hotel rooms. Both are unpredictable, but family-run lodges have even bigger chances of unpredictability, unstandardization, and restrictions. Now you aren’t dealing with the staff, you are requesting a family, who takes things personally. Simply put, some host families have been pretty scary. Having said that, for the past ten days, I was in two different homestays in the Wayanad district of Kerala.

On the road, never say never.

“Let’s not make anything of this. Let’s get our things done so we move forward.”

My partner

All around India, we can return to a couple of hotels anytime, but perhaps to only one family. And when we go back to a place where we have stayed before, its people recognize us, welcome us, and we are at home immediately.

How do we make ourselves at home in such transience?

We humans are screwing up the planet, but we know how to keep ourselves safe and secure.

Now after getting into a new place hundreds of time in the past three years, we make every home quickly ours.

As soon as we get in, we put down our backpacks. In the later section on how we have packed for the road, I have detailed our packing. We bring both backpacks and laptop bags from the car. After carrying two separate laptop bags for three years, recently, I put my laptop into my partner’s shoulder bag—because that’s what we were doing every time we got down at a park or climbed up a mountain to work in the green. Now, we have to bring only one work bag to the room. If I need my notebooks and diaries, I bring mine too.

Sometimes, we realise the simplest of things in months, even years, and I find that amazing. Even after three years, we are constantly updating, modifying, and recalibrating the arrangement of our things, their positions in the car, and what we take when we check in. There’s always scope for improvement, and we can never say, ‘This is perfect now.’

I take out my body cream, toothbrushes, and water bottles and arrange them in the room. If we are staying for more than one day, we get out our two pillows, too. They are our back cushions on long drives, but you are reminded of their original purpose when you get one-foot high or stone-hard pillows in your room. Beddings around India have broken our trust. So when we are doubtful, or lizard droppings shine on the bed even though the caretaker denies it, we take out our bedding bag.

I can make perfect sit-outs of uncomfortable sofas in hours. We get water bottles filled at night, so early morning, we don’t have to call or knock at anyone’s door for water (I gulp litres soon after waking up). Somehow, I mostly find a bed facing the east. Recently, in a house with multiple beds still in their plastic (I guess to keep them clean), the only bed with a mattress out of its plastic became our bed for three days. It was also the one on which the first sun rays fell.

When almost everything changes around us frequently, nature is our constant friend.

Fruits have come with us a long way too. I increased my fruit consumption as I started focusing more on a healthy life. Now I eat fruits because I love them.

I buy fruits while on the way. When you drive as much as we do, you do not want to go out ever again (our feelings change just overnight though). So we buy whenever we can and keep.

This is one of the benefits of a traveler’s life that I get to eat fruits and vegetables from all around India. I mostly pay a wholesale rate for the best fruits. Sometimes, I live with a family who owns an orchard, or while driving on the highway we pass trucks and wholesale vendors providing fruits at lower prices, and many times, we buy directly from the farmers who now stand on the highway selling items by the basket. Rarely do I have to visit a traditional fruit shop in a city. For someone like me—who consumes kilos of fruits every day, and so really does buy in wholesale—this access to India’s best fruits is a privilege.

Our room and car overflow with a rainbow of fruit. On the road, when we don’t find a place to eat for miles, when we arrive late in accommodation, or while hiking/walking in the sun, or just on a busy work day, the fruits that we either keep cut in a box for the journey or those we wash and gobble on the go are a life savior. (As I write this, my mouth waters imagining the taste of the Kerala pineapples and mangoes that now sit in my room.)

For two homeless travelers, the overflowing packs of fruits are a comforting sight. They assure us that we won’t starve.

Everything is psychological if we look at it. For sure, the presence of our things in the room makes it our home immediately. I even hang our night clothes, and the moment we are in, we take out our indoor slippers. A cup of chamomile tea before bed snugs us right in. How do we heat water? In the absence of a stove or a hotel-provided kettle, we bring out our own.

Our friends lovingly gave us a kettle they weren’t using. Now, it stays in the kettle bag and comes out on cold nights or sleepy afternoons. In a recent wooden hut, the geyser switch worked as a plug point (we weren’t sure if the other charging points would take the higher wattage).

Talk about finding a solution!

In every new place, we soon get into a sort of a rhythm, a rhythm that has been developed with habit, by traveling often, by doing this enough times, that rhythm then takes over, and we merely dance to it.

What we are still wrong about is the time we would need in each place. Often, we are extending our stay or leaving half-hearted. If we could just stay for one more day!

After three years of itinerant living, still wanting to stick around to places and be able to feel at home anywhere is a good thing.

Working on the Go

Beyond finding good stays, the most challenging has been to work on the go.

My partner has a full-time remote job. His calls and meetings can be so incessant he won’t even get up for lunch. This doesn’t have to be the nature of the work, but it has been so.

Checking out of a place to get to a new one, going on a hike, and even buying groceries during the lockdowns (we were on the road during the second COVID-19 wave) becomes hard. At the beginning of our journey, we fought in Mashobra village in Himachal over, “You can’t take out even one hour to buy groceries and lunch” as I have written in the linked narrative. When we do go out during his busy work day, we have to be extra patient with each other, or a disaster is imminent. Suddenly, a storm might make it difficult to climb, networks might disappear from the area, or there is always the back and forth at the new place.

Initially, my partner was driving us to all the places, and I was finding guest homes, negotiating, talking, settling us in, getting the place clean, cooking, and so on.

“Do you think you are the only one who has work? You don’t care about my work at all.” This was my usual criticism.

My partner—who couldn’t change the schedule of his work—repented his behavior. I repented my harsh words. On our four-month trip through the Himalayas in 2021— we were traveling faster, moving often, and hiking a lot. Afraid of missing out, we stayed in most locations for a couple of weeks and did a lot. Climbing apple trees, admiring blood moons, and getting on daring trails were our day-to-day.

My Himachal Pradesh articles can be found here.

Amidst so much, we used to be stuck in long, miserable discourses of blaming each other and apologizing to each other.

“You don’t care and you take me for granted,” and “I didn’t mean it and I didn’t know” were our favorite phrases.

Not anymore.

My partner cares for my work and progress more than I do. His inability to pause his work had nothing to do with me. Now, instead of being stubborn—if you won’t adjust, I won’t—I depend on the flexibility of my work: I can write earlier or later in the day to keep us going. He takes over the weekends.

The idea is to keep our lives running peacefully. And every so often, I can say, “You have a meeting? I’ll just go get some mangoes.”

I accept the host’s request to join the family for dinner around a bonfire. On my partner’s behalf, I give the excuse of his work. An afternoon walk around the cottage’s coffee estate or picking corn with the village women is my solitary time, and I don’t even ask him to come.

Sometimes, we still argue over managing the day, but these conversations aren’t as long drawn-out as before.

Changing homes or locations on weekdays and exploring the local places is unavoidable, even desirable.

“I just want to walk this way and see what’s here,” I often say, pointing to a path or street around a new guest house. Or if we leave tomorrow, today is the only day to see that temple down the mountain. The local events and festivals don’t follow our work schedule either.

At every destination, my partner and I patter nonstop about what we want to see, do, try, and figure out. We are still learning to fit leisure, work, and exploration with each other.

From that hotel on the outskirts of Mysore where the staff was surprised that we didn’t go sightseeing, we checked out on a weekday. Any more day in that guest house would have been blasphemy. On such mornings—most checkouts are by noon—we get ready, work, pack, leave, and drive to a new hotel we have shortlisted or stay out. If something works out soon, good enough. Mostly, we find ourselves in a park or a garden, in the car parked on the roadside, or perched on a bench under a tree. We work some more, shortlist a few more places, even explore the destination, and then see one or two guesthouses and finalize. Sometimes, we check in by seven or eight pm, and on those days, we have to be each other’s and our own best friend.

That day, we checked in much earlier though and took a long afternoon nap. But I will never forget that Friday when we left our friend’s home at ten am, drove to another city, saw its places, tried on different hiking shoes in stores, worked in a mall, ate at a well-known food joint, and then, when we didn’t like any accommodation, drove to Himachal, checking into an amazing hotel by eleven pm.

We were exhausted by the end of the day. But getting into a good home is more important than a rushed check-in.

Finally, in bed, we said, “I can’t believe we have done so much today!”

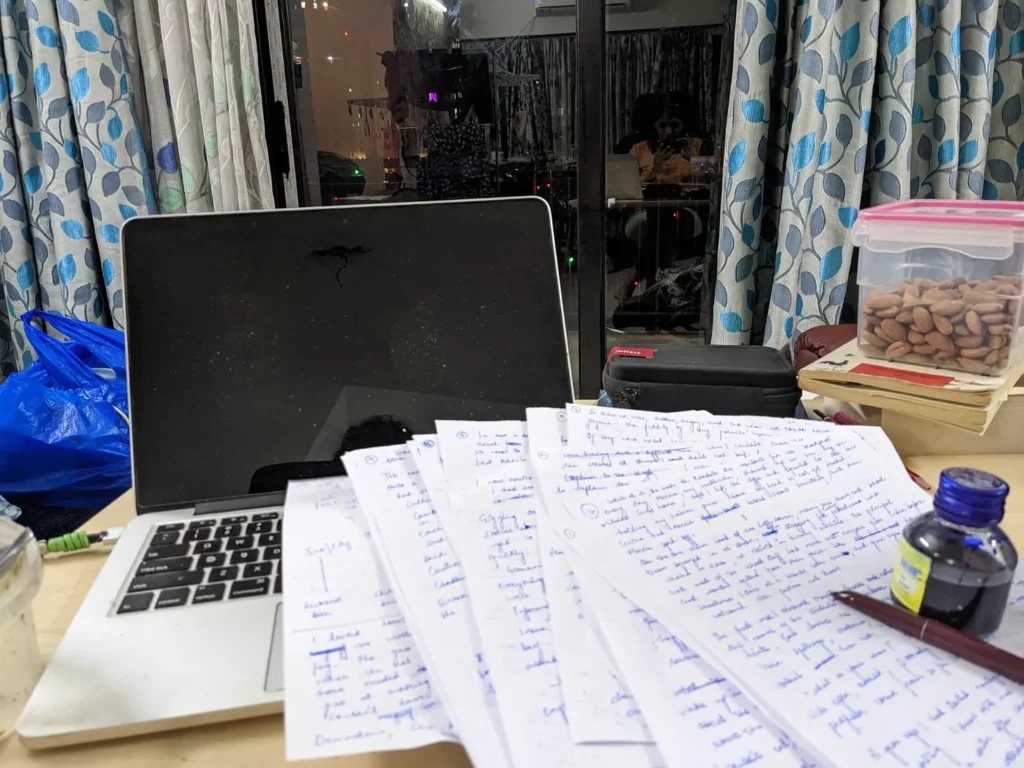

During the last two years, a big creative writing project made it difficult to move around so freely. I started it in Pondicherry in March 2022 and wrapped it up in mid-October 2023. During this time, we stayed put at locations and homes for longer than intended. I hadn’t planned to get such a project on the go. Now when it was offered to me, I couldn’t say no. I had to do it.

How did we manage on the road without a home of our own while both of us were so buried in work? Was it worth it?

Our slowing down for work began in Pondicherry in March. Overall, we stayed in the area for ten months.

Were we still exploring and traveling or just living?

Right before the project, we lived at a beach in a fishermen’s colony for slightly over two months. Though we didn’t tick mark the list of things to see, we lived with locals, visited the ancient grocery market frequently, bought greens I had never seen before, walked around in the neighborhoods tourists visited especially, and went to the beach every day. At 4 am, we were woken up by the calls of the fishermen calling each other, already taking out their boats into the sea.

Maybe someone won’t consider all this as exploring the place. I do. When you buy fish from the street fish market, try to get it scaled and cleaned by a woman who is already scolding you in Tamil, and then elbow your way through that busy hotchpotch, you get the real experience of the destination.

In Pondicherry, I also picked up the car again after my driving course in February 2021. In between, I didn’t drive due to COVID restrictions, mountainous paths, and just the inertia of not having driven for long. Though I started taking the car out at five or six am, mostly, we returned by nine. During those morning hours, we caught the city of Pondicherry in action.

From the beach, we moved to Auroville, a community on the outskirts of Pondicherry. Established by Mirra Alfassa in 1968, a follower of Sri Aurobindo, now people from about fifty-nine countries live in Auroville. Many of them came as early as the 1960s, following the founder. Though the idea was to make a space where all humans will live in peace as equals, now the community represents a disillusioned diaspora from the world who wants a different life but doesn’t want to work for it. Trouble in Utopia: an article about Auroville on Slate.com by Maddy Crowell ends on the perfect note,

“That place (Auroville),” he (a bar owner in Pondicherry) waved his hand at the ground. “They’re all looking to be cured. The ones who are cured, they leave. The rest, they’re stuck.”

“Cured of what?” I (Maddy Crowell) asked.

“That,” he responded, “is the question.”

In Auroville, a hut in the middle of a dry forest—with no running water connection, an outdoor cold shower, and an outdoor little stone basin on the earth to wash utensils—became our home for two months. It had a simple cement floor, a mattress for bed in the ventilated attic, and long meshed openings in the walls covered with thin georgette clothes. There was no wifi connection, our phone lost network often, and we were in the middle of a forest with frequent power cuts. Not that we had more than one plug point, two faint lights, and a standing fan we never turned on.

My partner wasn’t excited by such raw, rustic living. But I had gone to Auroville—a place known for unique housing solutions—for such down-to-earth homes.

“I know you’ll never stay at this place. I always adjust for you, but you’ll never compromise for me.” I wiped my tears in a temporary accommodation. We had just visited the hut, and its squat toilet with no hand shower had broken my hopes.

“Let’s take it,” he said, consoling me.

“No. You’ll complain forever.” I shrugged his hand away and curled up on the bed, my laptop waiting for me to resume the draft of What is Good Writing and a Christmas bonfire leaping high in the sky beyond the window. The past few days in the Pondicherry house where we had to call the police had been tough.

My partner insisted he would adjust. We took the hut for a week and then kept extending it.

Living in that jungle hut needed a lot of effort and patience every day. Our host was an old French woman, and trying to coordinate, raising the problems, and convincing her that yes a big fat rat did sneak in every night through the wall mesh deserved a post of its own. I have to write it soon.

When I looked beyond the living issues, the natural life breathing around me absorbed me completely. Through my daily walks and explorations that began at dawn and went into the night, I studied how a forest breathes, which animals are shy and which are friendly, and how the light filters through the leaves throughout the afternoon. Mushrooms, moss, and moths all intrigued me.

When we were not busy staring at snakes outside our cottage or watching the stars from our bed, we attended local festivals and art activities and finally explored parts of Pondicherry we had not seen while living in the city. One fine day, when the host shouted at me that I was spoiling her Sunday—the shower didn’t have water, and it was pending to be fixed for weeks—I finally put my foot down. A noisy neighbor in the other hut who thought only old people like to be quiet didn’t encourage me to stay either.

From the forest, we went to another guesthouse, which was at the edge of the jungle. Now, we didn’t have to bring our own water cans and gas cylinders, or do gymnastics with phone in hand, looking for internet. Wifi and electricity mostly worked well, and the staff looked after the rest of the things with a little cajoling.

That guesthouse was our longest stay during the three years. We stayed in the same room for six months, and my big writing project took wings from this room. I woke up at dawn, walked around the lake, and admired the snakes and turtles that showed themselves to me. After a shower, I wrote with a cup of black coffee on the table.

That was my schedule for most of the six months. In between, I attended Tamil festivals, classical music events, and plays in a nearby theatre. I walked and biked through the mud lanes curling through the forest, letting myself get lost and discovering a new path daily. No one stared at me, even if I wore short skirts or shorts. I was free, at least wardrobe-wise.

Every Friday, my partner and I gave the keys for the weekly cleaning and biked to the community’s grocery store. Pulling ten to twelve kilos of fruits, vegetables, and cheese on an uphill slope in the sun, we broke into sweats. We drove to the city to buy mangoes from a wholesale truck. Every time some ten kilo was picked up.

With a friend from Columbia, I walked amongst the trees at night without any flashlight. In the darkness, the silence of the forest was even more profound. With another friend who was old and in a wheelchair, I watched the guesthouse lake, both of us quiet. I stole drumsticks, lemons, and papayas from the trees outside our room and cooked to my heart’s content. In the jackfruit season, my partner and I carried empty bags and a knife and biked to the forest jackfruit trees we had marked on our mental map.

“Be quick,” my partner said to me as I tried cutting a large jackfruit, its spikes poking my palm. I got a big jackfruit free, but the white sap oozing out of its stem made everything sticky. I pulled another smaller one, too. We quickly put them in plastic bags, shoved them in the side bags of his bike, and pedalled hard to our guesthouse singing, laughing, and hailing ourselves as the heroes we are. I prepared the jackfruit fry with onions the way my mother does.

I didn’t leave home to become a jackfruit thief, but I don’t mind the title.

Though we were too shy to be seen taking the wild jackfruits, now I know anyone could have taken them, and no one would have minded. If I say life is a bit like that too—treasures are waiting everywhere to be found—you might not believe me.

The journey sounds like a dream. It mostly was, if not for the people of Auroville. Though I have a couple of posts on Auroville in drafts, this article is a good place to mention that when you stay in cultures different from your own, or when you don’t follow the popular culture practices, you stand out and that may not be the good thing always.

For example, my partner and I don’t fit into the culture of my parental home in Uttar Pradesh. Instead of a sari and bindi—the conservative markers of married women in North India—I wear pants and don’t even put on earrings. I have quit my job to write, we live out of a car, and we cannot be found visiting temples or praying. Our unconventional choices put us right out of the circle of people in any community. No matter whether we are in the East, the West, the North, or the South, language, religion, physical appearance, lifestyle, work choices, and eating habits segregate us from others.

In most places, the differences are obvious as we are outsiders. But even in experimental places such as Auroville—which claims to be a universal town where men and women of all countries are able to live in peace and progressive harmony above all creeds, all politics and all nationalities—we didn’t fit in, to our surprise. Irrespective of what the community said, the fact that they are a group, made them particular and exclusive. As the residents value less work and depend on external donations, we were judged for working online and working hard—the linked post has more details.

We still resided in the place for eight months. Call us hypocrites? We were taking what we needed from the system. Auroville is a big place with about three thousand people (as of June 2023). The idea behind the township was to have a space for all beings from around the universe and the capacity imagined was 50,000. However, due to in-community conflicts and slow growth, houses are fewer and green space is much larger. Think of the township as several buildings scattered around a large forest. I could walk for an hour without being seen by another human. Most mornings, I cycled to the internal grocery center and bought fresh cow milk and Malabar spinach. The cultural activities provided enough entertainment. The whole place was my playground, and all its turtles, owls, and tortoises were my friends.

Even by the end of six months in the guesthouse, I hardly had one human friend.

Did I get a sense of belonging? Within our large room equipped with a stove, yes. I put on classical music and took long hot showers in the dark. As the rain poured outside, I burnt candles, sipped wine, and read on our porch, sometimes only disturbed by the lost owl looking for a shady branch. The library was my favorite place where not only I played with the in-house cat but discovered forgotten writers from the past. I cooked for as long as I liked when I liked.

Outside our space, the natural world adopted me.

That guesthouse that we could extend month by month rooted us for a bit. Only at the end of August, did we leave Auroville to drive to Calcutta. We were to park our car in Kolkata at a friend’s house from where we were flying to Vietnam for our birthday month.

That one-month trip delayed me from finishing the project sooner, but then I always question myself: what will I get by completing a work project as soon as possible? The idea of meeting all deadlines sounds great. That I could do it in the least possible time, faster than everyone else makes me a hero. But when I know I would need a break, relaxation, or recharge to enjoy the process, I pause.

The journey to Vietnam wasn’t the most relaxing option. We planned to figure out things on the go. But I had been in Pondicherry for months. Though still considered outsiders in the community, we had to make ourselves at home every day. Still, my routines were set. Neither did I have to look for a home or food every day. The idea of traveling to a new place thrilled me (I had been to Vietnam in 2016 but only for ten days.).

From Pondicherry to Calcutta, we followed the east coast, drove through the rural West Bengal, and stopped at ancient places of Andhra and Orissa. I didn’t know that caves and monasteries as old as the 6th century CE exist just on the roadside—right on the highway—for a common man’s view and perspective.

At my college friend’s home on the outskirts of Kolkata, we were truly home even though for a night. We unpacked and packed, prepared our car for storage, and took our last B12 dosage injection (we had to take five due to the deficiency as per the latest medical report). We booked a one-way ticket to Saigon and a family-run hotel for three nights and flew.

Vietnam was much more crowded than how I remembered it from six years ago but some unexpected adventures came our way. Our journey began with some fishy adventures in the city of Saigon. On my partner’s birthday, we cycled in rain through the little island we were staying on, stopping occasionally to play pool with the locals. Back at the riverine guest house, my partner slept off drunk on rice liquor while I drank into the night with the hosts and guests and finished the home-grown prawns cooked in coconut caramel sauce in a clay pot. On my birthday, we biked, again in the rain, on the muddy trails of a national park. We were returning from a natural water pool, drunk on beer given to us by a family. Balancing the cycle through the sludge, I sang in Hindi about the glory of my partner and of the fresh and lush forest that swayed as if rejoicing with us. My phone got soaked. For the next three weeks of the trip, we had one phone only.

I didn’t repent pausing my project, as you can read in the newsletter Traveling in Vietnam: Chopsticks, Fish Noodle Soup, and Coffee I published after returning from the country.

Back in Calcutta at the beginning of October, right at the start of Durga Puja celebrations: the biggest festival of West Bengal which we were fortunate to attend, we continued staying with our friends. Thankfully, they didn’t kick us out. They encouraged us to stay.

“Why are you leaving? Go when you have figured out a good place,” My kind friend told me as the pressure cooker in her kitchen whistled.

I accepted her generous offer, gratefulness filling my heart. My partner was embarrassed. “Maybe we shouldn’t stay for so long,” he said, scrolling a hotel booking app.

“These are my college friends. We can be here until we find something. After the vacation, some stability will help me,” I replied.

Now we didn’t have to get up and think, where should we go today? All I had to do was make a cup of tea and write. By the time, the house help arrived, I was at my desk in our room.

I wrote in longhand all days of the week from early morning until I slept except when I had to direct the cook for meals and to walk around the lily-studded lake channeled directly from the Ganga river flowing a hundred metres from home. In the evening, I copied the stories to the laptop word by word. Even the helpers of the house were surprised if I was not at my desk. My partner worked outside on the dining.

A month passed by. That month-long vacation in Vietnam was now a hazy memory.

My friends went to Delhi for two weeks to celebrate Diwali with their parents. I started searching for guest homes. I would have to leave, too. But they said, “No, you stay. The house is open.” Again, I took their offer. We had been looking at accommodations in Bengal and further eastwards but had liked nothing. Maybe we hadn’t looked that hard. We weren’t going to be homeless even if we didn’t book anything. Now, that was something.

On Diwali, my partner and I drove to the main Calcutta city (we lived on the outskirts).

“Let’s have some Diwali fun,” we said to each other.

As we stood by the shore of the Ganga absorbing the smell of the river, dolphins swam along the coast. We were overjoyed. “Look, look,” we cried and held each other’s sweaty hands.

Such moments—when the universe exposes its true face to us—aren’t rare. One doesn’t need to travel to be amazed by this world either. But travel has made me recognise such ethereal instants faster, and I embrace them with open arms.

On Diwali eve, my friends’ home and our hearts were all lit with the lights from the lamp and the homemade festival food.

Gestures of kindness go a long way, and we are nothing and nobody on our own are only two of the lessons the road has taught me. Patience from everyone was needed every day, and where is that not true?

All during the months in Kolkata, my mother would ask me: So you’re still there? She hadn’t heard or seen anyone putting up with their friends for months. But now when I tell her I am at a friend’s home, she doesn’t get surprised. I think, somewhere in her heart, my mother knows, like me, that we have friends everywhere and perhaps a home, too.

In mid-November, my partner and I, finally, left Kolkata. Though we had booked a homestay in Guwahati—we both wanted to explore the Northeast—we got doubtful on the way.

“Why are we going to as far as Guwahati when so many others places fall on our way? Would we just pass by them?” I asked my partner as he drove.

“Not sure. Because we found a place there? What do you have on mind?”

“There is one nice apartment in Siliguri. Want to try it out?” I asked, my eyes glued to the phone screen.

We didn’t know anything about Siliguri, the city that connects the rest of India to the eight Northeastern states. A couple of hours later, we were there.

First, we stayed for two days and then ended up living in the same apartment for two and a half months.

The lovely little two-room place had its issues, some of which were hard to ignore. Disruptive neighbors, an outdoor toilet, no geyser even in winter, no good work chair, defence helicopters vrooming above our locality five to six times a day, garbage strewed around the building, and the worst: a host who rang our loud doorbell even if his cat sneezed and who tried to replace every item: from as small as foot mat to refrigerator and even electrical wiring while we were in the house.

I could count the number of days the host didn’t show up at our house. Every time he decided he was having an emergency, I needed a couple of hours to be able to breathe again. Meditating didn’t help. He knocked exactly the second I sat down on my yoga mat.

If we had a home, we would have gone back to it. But my partner and I didn’t have a house.

We could have traveled further towards the East. But some friends from Assam had told us that traveling impromptu in the Northeast isn’t the easiest. They said the internet might be unreliable, you can’t always find a place to stay in remote areas or even convey what you are looking for because of language gaps, and so on. Unsure if we would be able to figure out that unknown part of India while being buried in work, we continued in Siliguri.

Other accommodations in Siliguri didn’t seem good either.

We tried to work within our limitations, took deep breaths, and stayed put. That was the need of the hour.

Did we feel restricted and hopeless about not having our comfortable home? Yes. But most of the time, we were trying to make do with what we had.

In hindsight, I can’t believe I endured that Siliguri home. It sounds impossible. But I have learned that at the moment you are just trying to survive, as I write in this letter on the vicissitude of seasons. Rather than spending energy on ‘How it could have been,’ you think, “What can I do now?”

Not having a home has been a choice. The host was interruptive, but he wasn’t a bad person. I lived in that house in the hope that one day he would appreciate my hand-folded pleas to let us be. Despite everything, we couldn’t give up on him. That’s how hope works: as long as you have it, you keep going.

Also, the circumscribing open grounds that were littered but that had turned copper in the winter, and the stream curling through them mesmerised me. The road to the house ran through the Mahananda Wildlife Sanctuary, and I drew my energy from the wilderness. Whenever I lost focus, I sat down again.

Our time in the apartment was over. We still hadn’t figured out the next destination or home.

Anyone can see that neither Sagar nor I are big planners. We do as we go. In our defence, the one or two plans we make always fail. We had planned the start of our trip in 2021, but then the delivery of our car took its own time, and the pandemic took its turns. At times, we book a stay for a week, but somehow we can’t leave before three. On the rare occasions when I book in advance, I repent leaving the current place.

We have mostly learned to leave it all up in the air.

The unpredictability is hard to take on sometimes. But both of us like the freedom that any morning we can decide to stay or pick up the car and go wherever we like. We bear the cost of the freedom.

After the apartment, we stayed for two days in another home in Siliguri. Its kitchen had so much dust and cobwebs, that we decided to sleep hungry. As leaving the city on a busy work day without knowing where we would go made us anxious, I booked a large room overlooking a humungous tea estate for two days.

“I know it’s expensive,” I told him as we sat on the dusty dining table, making sure not to touch more surfaces than necessary.

He said something along the lines of No Shit Sherlock and started recommending other accommodations. All of them sucked.

“Let’s just loosen up our pocket a little. We can always tighten our budget later. Assume we are spending on our anniversary. This is a special occasion. Let’s make things easier for us,” I convinced him and joked, “And you call me penny-pinching?”

Our anniversary was a couple of weeks later. We don’t necessarily go to a new place for celebrations. But then we needed the break.

In the lush tea estate, I found the treasure of nature. Sagar took off, we plunged into the large bathtub for hours, drinking wine, and we went on long walks through the tea plants.

From Siliguri, we went to Kalimpong, a mountain town in the Himalayas of West Bengal. I am almost scared to write that we finally drove on a weekday and argued on the way. But this time, we had a room in a home booked for two nights. Our host called us every half an hour throughout the day.

Every home in that vacation town was high-priced. Locals from Kolkata and other nearby cities thronged to Kalimpong in holidays.

“Four thousand per night? Nothing is less than three thousand.” We said to each other as we browsed for more guest houses in Kalimpong after dinner. At that time we didn’t know our light dinner would cost us six hundred rupees.

“Bonfire, meals, villa stay. This place isn’t for us. People here would expect us to chill, eat, and spend.” Our host had already told us he was unhappy with us. “You guys are workaholics,” he had said.

I tried explaining to the kind and suitably enthusiastic Nepali host that we stayed at one place for a few days so that we could see as well as work. After all, we hadn’t paused our life to resume it post-vacation. We were living while we were going.

He wasn’t convinced.

Early morning, I turned on the little heater, plonked on the sofa, and wrote. We checked out after breakfast around a bonfire and memories of a homemade scramble tofu I haven’t found again. A bit later at a cafe, I zoomed into the map and searched ‘hotels nearby.’ In an area close to us, red markers mushroomed in a blink. The hotel-studded space was the city of Gangtok.

Sagar and I looked at each other and said, “Something might work out.”

I shortlisted a couple of hotels that looked quiet, had workstations, and promised great views.

A room with a window is a writer’s best friend. You may not go out for hours or days, but you can still see the world.

None of the shortlisted hotels worked out. But when you wish for something so hard, the universe makes it happen. We landed at a hotel at night and were welcomed with the traditional silky Sikkimese scarf khata.

Then we didn’t know that room 405 would be our home for three months.

By that time, I had stopped expecting much from accommodations. I checked everything and asked for what I needed.

“Does this feel fresh to you?” I checked with Sagar while sniffing the bed sheet.

He bent down, put his nose to the bed, and said, “Feels fresh to me. Look at these creases, they aren’t there in old bedding.”

He was wrong. As he caressed the bed cover like one touches an old friend, I didn’t correct him. That sniffing was our first litmus test.

Suddenly, the phone rang.

“Ma’am, what would you like to have for dinner?”

I don’t tell people not to call me ma’am anymore.

“I’m still trying to figure out if this bed sheet is fresh.” I laughed. A chuckle rang from the other side.

“Let me call you back.”

Staff came with in-house reusable water bottles filled with warm water, a gesture exclusive to that hotel and that we appreciated much in the cold weather. I breathed. Thankfully none of that mineral water bottle nonsense. The guy said the bedding was changed after every checkout.

“Are you sure this is changed?” I asked him, adhering to my promise that I wouldn’t take even the obvious for granted.

“Yes. Do you want to change it?” He stood at the door.

“If you say it’s fresh, then no.” I smiled, and he smiled, too.

The staff had a sense of humor. When we asked for a heater, it was sent to us immediately. We were told it was included in the tariff. It was fourteen hundred per night. The bed was comfortable, the bathroom was spotless, and the kettle and tea bags comforted us. In the morning, the unlimited hot water in the strong shower shook me out of slumber.

We extended our stay. And then again, and again, and again.

After a week, we left because we were ashamed of what would the staff think of us staying for so long. “Don’t they have a home to go to!” Someone might say.

After shuttling between three to four different hotels—none of whom could compare to the first one—on Sunday we went back. We were welcomed with love and smiles, and we didn’t waste any more time and got into our room, which was now priced at 1300 for us. Its workstation was behind a wall, separated from the rest of the room, and the sofa chair and the desk were on two ends, distancing the two of us substantially. None of the other rooms matched up to it.

I picked up my work routine again. Our one-meal-a-day schedule saved our lives—I write about our food habits in the How do we manage food on the go section. The nearest good food eateries were in the main market square a twenty-minute downhill walk away. Our hotel’s restaurant wasn’t that great beyond the basic parathas and was expensive too. On a cup of instant coffee and apples, we worked until we could and walked to lunch.

Our experiments around the food joints brought us down to a few places we frequented. Mostly we devoured Nepali, Bengali, or a Rajasthani thali meal. Though we are not big rice eaters, for weeks we had a Nepali meal that a loving waiter served us. It had rice, dal, pickled radish, onion, a vegetable preparation, and churpi chutney: local cheese churpi sautéed with tomato, onion, and green chilli. We could take refills.

After Nepali, came the turn of Bengali thali. The restaurant guy served fresh chapatis in place of rice as we requested. The meal had dal, vegetable preparation, potato fry, salad, and chapatis: all unlimited. Most often we took second servings of lentils and vegetables and were replenished with hot portions.

Then we started avoiding both of those meals, slurped thukpas everywhere, and tried some fish thalis at other places. We dreamt of home food. Simple rotis, lentils, kadhi: a chickpea flour curry made with buttermilk, onion okra fry, and so on. We looked at each other with pity. We knew we wouldn’t get those North Indian dishes let alone together even individually anywhere.

One day, my partner and I went to lunch separately. When you spend twenty-four hours together, you want to break each other’s head. At that point, we both slam the door in the other’s face and each go our way. By the time we return, we have developed a bit of patience to talk about the issues, or we forget all about them.

Our travels have taught me important things about relationships that the linked article elaborates on at some risk.

That afternoon we didn’t talk. But the next day, we were descending the steep Gangtok gulleys, hand in hand.

“I have a surprise for you.” He smiled.

“What?”

“Come to this lunch place with me. It serves everything we were craving.”

“What?”

“Kadhi, bhindi, chapati, rice, salad. They give everything. You can ask for as much as you like. I took refills of it all, and they gave.” He was almost arrogant with his discovery.

“And you are telling me now?”

“We didn’t talk yesterday. You also had bitter gourd at the Nepali place,” he retorted.

“It was pretty delicious with rice and lentils.” I smirked, knowing he likes bitter gourd.

The Rajasthani meal place was exactly as Sagar had described. Simple tables and chairs in a small room. A friendly boy confirmed if we wanted thalis and then placed two plates with various vegetable preparations, lentils, kidney beans, kadhi, fresh ghee-swaddled chapatis, salad, pickle, chutney, and papad in front of us. Everything tasted as if cooked in my kitchen and was oil-free. I ate as if someone was pulling the plate from under me. We got unlimited refills, and most of the time, we didn’t even have to ask for them.

Within a week, we became patrons. We were given head nods as soon as we entered the eatery and served complimentary tall glasses of fresh buttermilk.

Can you believe we got such delicious and abundant food for one hundred and forty rupees? The place was always filled with people, and the boys served with a smile on their faces, insisting we take more.

I often told my parents over the weekly Sunday calls, “I had so many kinds of vegetables and dal and homemade delicious chapatis that I would have taken hours to cook all of it.”

That experience was one of those special ones that glorify traveling, the one you can sell to others: “Was it possible to discover such a magical place in my home town and then use its features daily? No. At home, I’ll cook in my kitchen. But on my travels, I’m connected with the whole world in a more fundamental manner. I depend on others to be housed, fed, and cared for. And that’s the purpose of travel. To get down from our own cot of comfort and rediscover the world anew.”

Back in the room that had been cleaned in our absence, I made another cup of coffee. Looking at the incessant rain falling outside the window, I wrote until evening.

“Look, it is raining. We can’t go out.” I chirped to Sagar and read.

“Could you please switch on the heater. I’m cold,” he replied while working.

I obliged but kept the heater on low and the window slightly open. The cool fresh air from outside kept me up.

We stole days of fun in between. When we didn’t gulp down the sumptuous thalis, we got tofu, okra sautéed fry, and soups at an Asian place. Sometimes we got beer and potato crisps too. On weekends, my partner watched movies in the theatre solo, bought fruits by himself, and stayed on Netflix into the night.

Things did get out of hand sometimes. I would huff and puff back to the hotel—the downhill twenty minutes was now uphill twenty minutes—and couldn’t figure out if the toilet had been freshened with liquid and the bedsheets were changed. I can’t imagine staying in any hotel room for three months, but I did it then. From returning to the room and exclaiming, “Look how clean everything is, and we didn’t have to lift a finger,” I started going back to “The housekeeping has not done this again!”

Though I didn’t know better then, I should have requested certain fixed practices. When the housekeeping staff changed, we started returning to our room only to find garbage still lying around the dustbin and a wet bathroom floor.

When you stay in a home, you might not clean it for a week. But in a hotel for that long, my primary solace was, “At least, the space is fresh and clean every day.” After all, the room was not only our bedroom, but dining, workspace, entertainment center, lounge, shower, bath, and quiet space too.

One day after lunch, I said, “I cannot do this anymore, and I have followed up enough.” That’s when I knew I couldn’t take the hotel room anymore. My partner also wanted to leave. We wanted a change.

The room may not have been working out for us then, but we thanked the staff who gave us a home for so long.

After a three-night trip into the countryside of Sikkim on which I managed to get lost on the Himalayan slopes behind the house, we were on the highway again. Our destination was Himachal. We hoped to stay in a home in a village in Mandi district that had housed us for three weeks in 2021 during our four months in the state.

“I hope that house works out. There I know I can sit and write. We’ll get food, everything is peaceful, and we know the system,” I said to my partner.

“It will work out. Don’t worry,” he replied.

We didn’t call the family before leaving for Himachal. If it wasn’t their house, it would be some other house. We trusted the state. Its people had shown us enough kindness enough times.

On the way to the Himalayas, we drove through ripe corn fields of Bihar and arrived in Uttar Pradesh at night. In the next couple of days, we stopped at Agra: for the Taj Mahal and Lucknow: for the food. Further on in Haryana, we put up at a friend’s house for a few days, eating homemade food and working in their home office.

Himachal did house us. During the first month, we revisited the Rewalsar Lake and Seven Lakes we had seen before, living at monasteries and family accommodations. Many days, we woke up at five, found our way to hidden lakes, and returned by ten am to work. One day when a Rewalsar host said “This is how it works here you can find something else,” we visited all the rest of the stay options around the lake. One monastery after making us wait for four hours said they couldn’t give us a room for a day. To begin with, we don’t commit more than a day.

With our things in the car, we headed toward Mandi, a town we liked and where we knew friendly hotels on the bank of Beas River. A plate of dal kachori (fried bread stuffed with lentils) and chana masala (chickpea curry) called us too. In the humid hotel that was once our home for two weeks, we were welcomed by familiar faces. We asked for a change of bedsheets, wiped the tables and bedside stools, and hoped to make the place ours at least for a week.

“Do you hear the river?” I asked Sagar.

“Yes,” he smiled and hugged me.

Though we were lulled to sleep by the river crashing against the stones, throughout the night, I woke up from loud banging noises. I couldn’t believe what I saw. Three to four big and small monkeys were sitting on the balcony parapet. One would throw himself against the door, hoping to send it flying. They repeated this performance as I watched, my mouth wide open. The ripe golden mangoes on our table were visible from the balcony through the glass window. The whole balcony was filled with monkey poo, and I couldn’t sleep for more than a couple of hours. If we hadn’t turned our latch from inside, we would have been robbed that night.

We left Mandi, driving towards Kullu, a town famous amongst Indian tourists. Touts selling river rafting on Beas River hailed us every two minutes.

“What’s happening here?” We exclaimed to each other and turned around towards the home that was on our minds.

“It’s time now,” I said to my partner and called the host.

From the beginning of June, we stayed in that village house until mid-October. Those were the summer and monsoon months when the entire news was filled with headlines such as, “another cloud burst in Himachal,” “flash flood drowned the village,” and “fifteen missing in the landslide.”

Our parents, of course, watched Himachal devastation headlines constantly on the news and were worried. The villagers were worried too. Mandi City and the surrounding villages suffered the most. As I updated in this newsletter, landslides were happening in the mountains around us often.

One day things got out of hand though. Every half an hour or so, I went to the hall where my partner was working and asked, “Did you hear that?” Both of our mouths were open. From our window that gave us a panoramic view of the road and the valley, we saw uncountable landslides. When we walked on that road later, we crossed maybe twenty landslides, at least.

Villages were swept away. Every day our host told us news of which kitchen was taken away in a cloud burst and which woman was swallowed along with her cows. Even a part of the mountain on which our host family’s home was located was broken down by the constant rain. They lost many of their terraced fields along with the hill. The family of the boy who brought us cow’s milk every day lost the entire slope with all their farms. They were worried their shop might be swept away too.

The night was the scariest when our host came to us at night, knocked at our door hard, and said, “The neighbors are worried about their shop. We are tensed about our home. If you feel scared at night, if something happens, do run upto us.”

Though my partner and I used to sleep in two different rooms, I slept at nine but he didn’t, that night we slept together. Now I might narrate this story as a tale to boast, or I might have teased the host, “You scared us last night!” But anything could have happened then. Eventually, the family was safe, we were okay, and the weather calmed down.

We didn’t tell our family all the devastation was happening so close to us.

What could we do anyway?

We were glad we had electricity. The water supply was revived after a week. Mobile connections went down. Thankfully our families did not call us during a couple of no-network days else unable to reach us, I don’t know what they might have done. The raging rains and the rivers swallowed up the roads which weren’t fixed for months. We had to stay put.

In such rains, thunderstorms, and the deafening roar of the wind, I kept my laptop plugged in and wrote. When the power went off, I burned candles. Water pipes had broken. We drove to the nearest petrol pump and filled our bottles from the water cooler there. When the cooler was dry, we refilled from the tap of an eatery. We collected rainwater for the toilet and showered in rainwater too. For the first couple of days, the host family brought us lunch. But when the timing didn’t work out with them, I cooked. As the fresh vegetable trucks had stopped coming, we cooked pulses and potatoes and whatever was available. Apples and pears were abundant in the orchard.

The weather offered isolation and dis-connectivity from the world. I took it and put all my energy into work.

Living without the basics, I learned we can adjust and adapt to any condition.

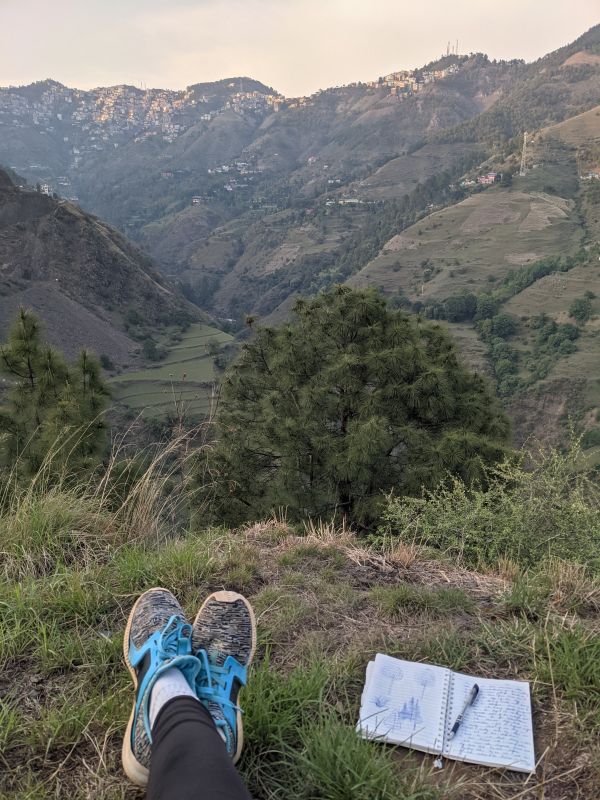

Also, I consider being in the lush Himalayas a privilege for which I even compromise on essentials. When it wasn’t raining, and it was safe, I went up the freshly washed slopes, ran around, clambered up and down shepherd trails, stalked wild animals, explored pine and cedar forests, climbed up pear trees, and did yoga. Every walk and exploration took me up and down the earth.

We are the healthiest and happiest in the Himalayas, especially Himachal Pradesh. Our expenditure is the lowest in the state. We choose offbeat destinations (yes there are still many), we live in rustic stays, and the affordable prices of the state help us go lower than our budget. As a self-appointed vegetable and fruit plucker of the family, I received a part of their produce daily.

In the past few years, the state has housed me for more than a year, and I could return to it anytime. The effect of climate change on the Himalayas is unnerving though.

The family knew us from before. But in the first week, they were surprised that we weren’t hiking about as much as we used to and that we were working all day.

“Everyone is running after money,” Aunty, the mother of the family and the one who interacted with us the most said one afternoon as we sat in their home drinking milky tea.

I found it hard to explain to a family who ran a hotel and restaurant for money why my project was less about money, or that I left a job with much more pay to do something of my own. That my project wouldn’t fetch me as much cash but I needed to do it.

While living in different cultures with people who don’t know us, we are used to hearing different opinions about us.

We are judged by our clothes, wake-up times, whether we get out to roam or not, what we cook and eat, et cetera. I can message a college friend in a second and say anything. My city neighbors knew I slept early. But the people we meet on our travels now—people we live with every day and depend on for food, water, and shelter—don’t know us at all. They don’t know where we come from, what is our education, how talented or decent we are, our family’s background or religion, and so on. They don’t have any reference to compare us against apart from their surroundings and neighbors.

Our challenge is even greater as we stay in rural areas and remote villages. Some village families we have stayed with had never stepped out of their district, let alone state or country.

When so many eyes are upon us—in most destinations, people stare at us from both sides of the road as we walk— we have to make sure to be kind, respectful, and amiable. Our behavior is our only weapon. The current generation of laptop workers isn’t much admired in the world—at least in India, where the common man works hard to meet the ends, and we, digital nomads, seem to have an easy life with money just flowing in as we type on our couches sipping coffee and kokum juice.

As we stay in most places for at least a few days, some people get to know us better. Others still consider us worthless wanderers. We are okay with that.

I wrapped up the project by the tenth of October. I had written almost everything I wanted to say, and I couldn’t be so diligent anymore. I was exhausted.

“Send it for now. Do more edits later.” My partner was proud of me.

After a two-day rest and sleep stop in Chandigarh, we went to my parent’s home in Uttar Pradesh. I hadn’t seen them for two years. My parents seem to have grown older. I made a mental note to see them more often. I still couldn’t help but resent every time my mother asked me to serve my husband first or when she offered something to my brother before me. Beyond these sensitive matters of the heart, the two weeks passed by in a whiff.

We were on the road in less than two weeks. Through Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, we arrived in Nagpur for my partner’s friend’s wedding.

After the celebrations, we turned back towards Satpura National Park. Both my partner and I saw tigers in the wild for the first time. Now we were headed towards Goa to be with the friends at whose house we had stayed in Calcutta. On the way, we took one-night stops in towns as we always do.

One day, after a night-long fight which kept me up all night (not to mention the loud receptionist and the ringing desk phone outside my room), my partner insisted I drive.

“But I haven’t driven since August 2022. You said relax and focus on work, now suddenly you want me to drive.” I cried.

We were in October 2023. More than a year had passed. Throughout the duration I had been working so hard at home, I didn’t want to work on the road, too. At that time, driving did feel like work. While my partner went out to buy groceries or food, I stayed back and wrote or ambled around the mountains, the coast, or the jungle.

This mental revision didn’t move my life ahead. After cursing Sagar for discouraging me from driving the past year, I couldn’t sit in the passenger seat anymore. It was now or never.

I hadn’t slept. I was angry. I was tired.

I took the wheel.

Once on the wheel, I drove as if I had been driving all along. Since then, I have been driving continuously. I have driven on highways, within cities, on mountain roads, and along narrow mud paths through the forests.

After waiting for years, I can finally say I have learned a life skill I thought I could never claim. Not because I didn’t think I could drive. But mostly men drove around me. Apart from Bangalore where every other car seemed to be driven by a woman, my partner and I see few women drivers in most places and hardly a couple on the highway.

In a culture where tasks are segregated by gender, you have to encourage yourself to pick up something that is unexpected of you. No one else will. Most families said to my partner after listening to our story (which we now don’t tell every time), “So you have driven from that far to here in your car?” He was the one driving us. Now when someone doesn’t assume and asks, we say, “Yeah we both drive.”

I let out a breath of relief after finally crossing the bridge.

We slowed down in Goa and celebrated Diwali with our friends, I resumed work after a long break, and we put up in an apartment for almost two weeks. I can’t tell for sure, but out of those two weeks perhaps I spent 200 hours on the beach. Then after traveling through some other parts of Goa, we drove to Nandi Hills near Bangalore for a friend’s wedding. From there, my partner left to visit his parents for a week, and I stayed in a hotel, enjoying my solo time.

I started writing the draft of this article in Bangalore.

In Bangalore, I worked again. Met friends. Bought things I needed. We went to the dentist. We drank beer in bars, paid for expensive food, and found good hotels with difficulty. We worked, we fell sick, we fought, we made up, we got our medical tests done, and we celebrated Christmas and New Year with friends. Then we left, for good.

To get into Kerala, we stopped at Mysore. My partner explored the town more than me. I stayed put, wrote, and rested on my period days.

After about nine days in and around Mysore, I drove us into Wayanad via the scenic Bandipur forest route. The border of Kerala and Karnataka is joined at the Bandipur and Wayanad National Forest. On both sides, the forest swayed as I drove slowly. At a natural water pool, a mother and baby elephant were drinking water. The road was beautiful, and the whole journey was surreal.

Since then we have been traveling slowly through Kerala. Three nights in a forest guest house with deer and elephant just beyond our fence, three nights in a home with a kitchen (we go grocery shopping, we cook, we hike to a viewpoint, I explore the host’s coffee estate with his sister), and seven nights in a wooden cabin by the lakes. We take safaris, we walk in the mountains, we see ancient caves, we let nature absorb us, and I take bird photographs. He works, and I write.

We are being slow. We are seeing, experiencing, living.

Now when I don’t go out one day, I don’t feel I am missing out as much as I did before. I am confident of our methods, and that other tourists leave the guest house early and come back late doesn’t bother me.

As I said: Travel has become a form of living for me. I travel, I live, I write. I can turn these phrases around in any order but they all mean the same to me.

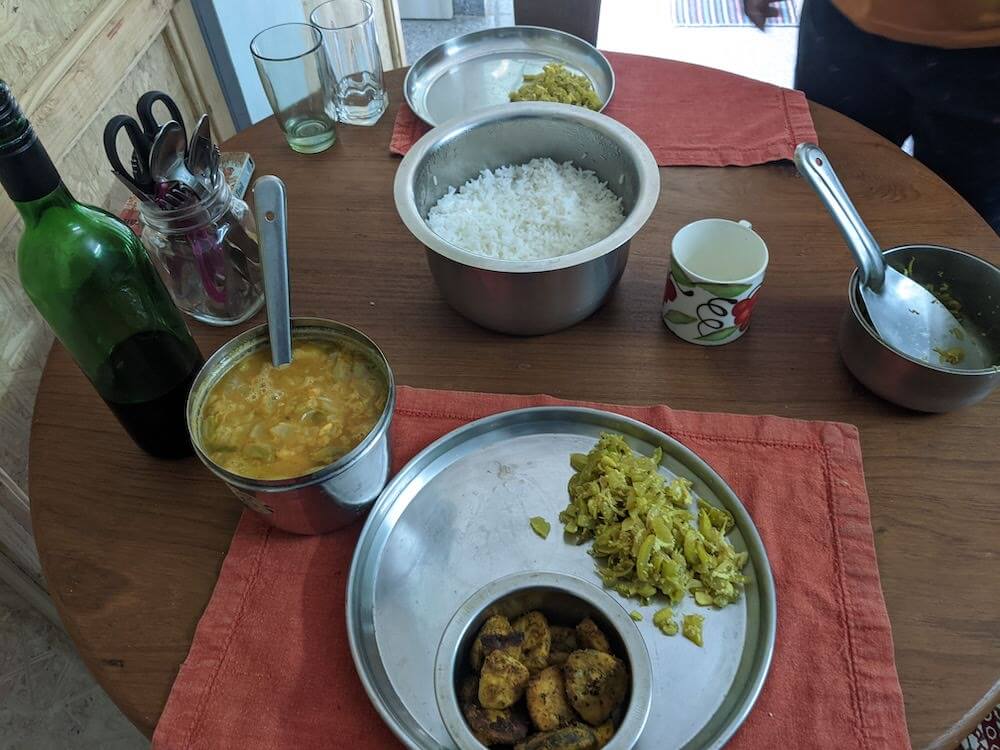

How do we manage food on the go?