In the Rohanda Village of Mandi District (Himachal Pradesh) We Come With an Aim, But First We Just Be

We went to the little village of Rohanda in Mandi district to hike to the popular Kamru Nag temple. The trek to the 3334-meter summit begins at various points above Rohanda.

On the national highway along which Rohanda lies, many budget hotels cater to short-term tourists who come for a night or two. They visit the temple and leave Rohanda. But most hikers are local devotees. Neither many Indians nor many foreigners know about the temple or pray to it as fervently as the Himachali people do. Let alone Kamru Nag, even the Mandi district isn’t well-known among tourists, and for that, my partner S and I were glad. Because since we had moved from the little villages of Shimla to Mandi, room tariffs had dropped, food had become more local, and hosts were kinder.

Kamru Nag temple is on the banks of a lake that is said to fulfill devotees’ wishes if offered money. Thus the Kamru Nag lake is guessed to be glutted with currency notes, coins, and even gold and silver jewelry. But we were there to hike in the wild. Two days ago, we had dared to climb up to the even wilder Shikari Devi temple summit from which we could have trekked directly to Kamru Nag. But such a storm raged at Shikari Devi that we had to wait in the government guesthouse for another night. When the rain stopped, we tried to hitchhike. But most car arrived full, and the rest were going too far away. The gentlemen in one car even said they would have taken us if only they weren’t so embarrassed to drink and have fun on the way in our presence.

So we descended from Shikari Devi on foot. The clouds still hung heavy above the peaks, and the paths had become sodden. Scooby, the mountain dog who had guided us onwards and whom we had taken the liberty to name, was missing, too. At a steep descent, S slipped on a mossy rock. By the time we were sure of having gone the wrong way, not only were we soaked in fresh rain but his right knee throbbed with pain. That day we found ourselves near villages —though not those from where we had started —and somehow reached down on painkillers, walking sticks, and locals’ advice.

Since it had only been two days since the fall, his leg still hurt. So that S could rest and see if he could walk the six kilometers up the steep mountains to Kamru Nag, we decided to stroll around Rohanda for a day. On the undulating mountain roads and tracks, we would understand more about his injury.

We could go to a doctor, but there was no swelling or external injury. The pain had reduced, and we wanted to wait out for a few days to see how the internal wound healed.

And our village Aukal — just two kilometers before Rohanda — looked amazing. Further ahead from our homestay, we had seen colorful temples, a stream gurgling over gravel, and many small eateries and fruiting apple orchards.

Admiring the mist that had enwrapped the forest, terraced fields, and the valley beyond our room, we went up to the family-run restaurant. But first, we had to cross people sleeping on the open concrete terrace outside the guest rooms. The host said they were Punjabis who had come late at night in a group of five. He had given the only available room to a newly-married couple while the rest slept outside as “Punjabis love to sleep outside.” And then he added matter of factly, “Now we cannot turn anyone away at night, can we?” Surely the host hadn’t been to big cities where hotels and, even, families turn away people at whatever time they like.

We extended our room for a day and had tea and a three-layered butter toast. In the big Mamleshwar hotel, our only option in Chindi village from where we had been coming, extra butter cost fifty rupees, while in Rohanda we got it for ten. In fifty, we got one big stuffed paratha.

We went down to our room, showered, rested, and after I had taken travel notes, we left for our walk with water and bananas. First, we went down a concrete path that curled up to the highway from the valley below. It took us through villages and vegetable fields. After looking around — but really being looked at more — we turned back when the little concrete trail became sodden with cow dung and radish leaves.

While going up the same way, I read that that concrete road was made in the previous year and benefitted thirty families. That was how small the village we had intruded was. No surprise that every villager wondered what were we doing there.

But our spirits weren’t diminished for our intention was just to see and instead of going all the way up to the highway — which runs until China — we went downwards in the other direction. On our right lay the jungle and on our left were village homes. In the garden outside one home, several women washed freshly-harvested mud-ridden radishes that when brought out of the tap, or the water tub, were as white as snow. But when they saw us, they stopped with the radishes dangling from their hands. As we had been in Himachal Pradesh for about three months by then, we weren’t surprised by their surprise. Speaking up was the only way to break the mist.

“Everyone is taking out radishes today?” I said.

“ Oh really. Who else?” The woman who looked the oldest and the leader of all asked.

“A house before yours too.”

After the usual small talk about where we had come from and where were we going and that Covid had given a little relief finally, she asked us if we would like to eat one. I nodded yes thoughtlessly. She grabbed four radishes with leaves, washed them well, and handed them all to us despite our protest that two were enough. “You are two, have at least two-two each.”

One more woman and a young girl washed and tied the clean radishes into bundles. I bit out a big piece of radish. It was bitter, but as I used to gobble radishes sprinkled with lemon and salt outside our school every day, I was just taking a ride back into the memory.

The family didn’t cultivate radishes for profit but grew a little in their fields. They depended on the rain because the brook was so far down from their homes that it couldn’t be drawn into the fields. As all the apples had been hit by the hail storm, they were spotted and would go cheap. Perhaps even ten-fifteen rupees a kilo, we were told. Those are the same apples we get in plainer states for at least a hundred rupees per kilo (or you can just pluck apples yourself from Himachal gardens like I did). A truck guy would come, fill his truck with the produce, and sell it in a wholesale market. They weren’t sure which bazaar.

We thanked the family, and further down, crossed many more women washing big bundles of radishes. They were all for selling because how much radish can one eat?

The plan was made soon though. We would get a couple more and ask our host to make radish parathas for us.

When the locals saw us — a young couple dressed in shirts and hiking clothes with a backpack — they each had their own reaction. A woman asked where we were heading and laughed saying that there was no market, nothing to see below. Some village women were so shy they waited for us to pass so they could turn around to complete their chores. And some older ones were curious and perhaps disgusted or stressed by our presence. “Who are these city dwellers who come from who knows where? Don’t they know covid has just been raging the whole world?”

We were so shy to ask for more radishes — even with the offer of paying for them — that we returned to the highway with the three we had.

My partner’s leg didn’t hurt yet. At a sweets and snacks shop, we ordered cottage cheese fritters, samosa, and two cups of chai. When the guy forgot to bring our food, he made up for it by frying our fritters in oil again. Cubes of cottage cheese were coated with a green minty chutney before frying and the whole thing was so tasty we saved three-four for later.

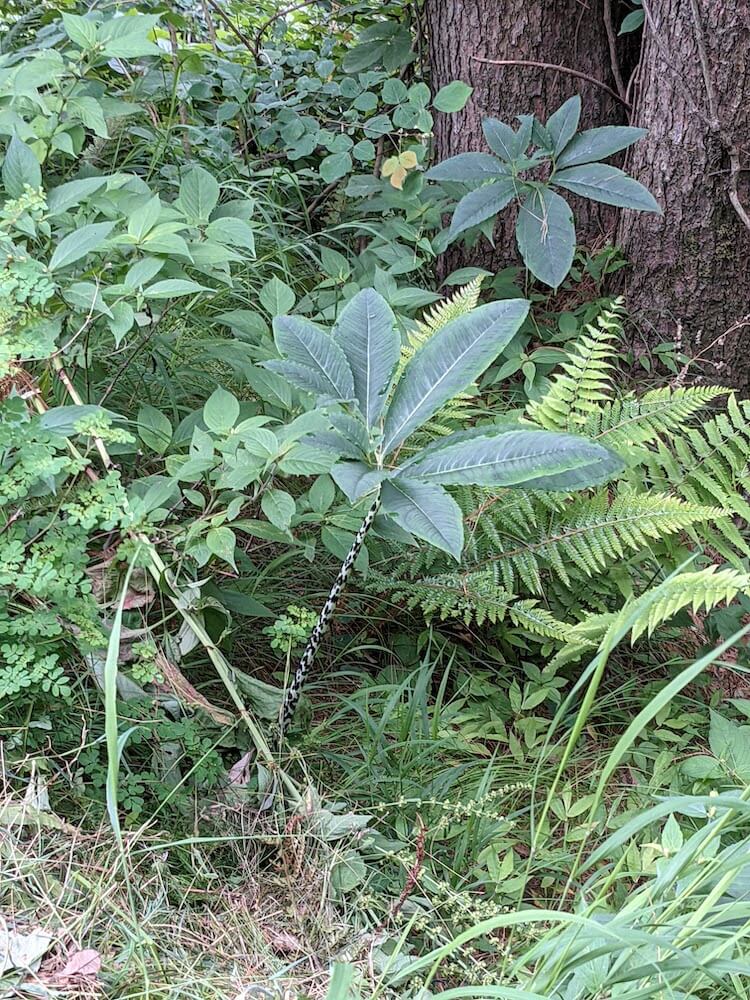

And then we walked on the highway fringed on both sides by pine and deodar trees. A lone school or post office would come on our way but that was all. Sauntering on that Himachal highway was so delicious because I could smell the fragrance of the forest, feel the carpet of soft pine needles under my foot, and as the traffic was intermittent, hear every whisper of my companion. Then there were the pink and red flowers and yellow and blue butterflies to watch, too.

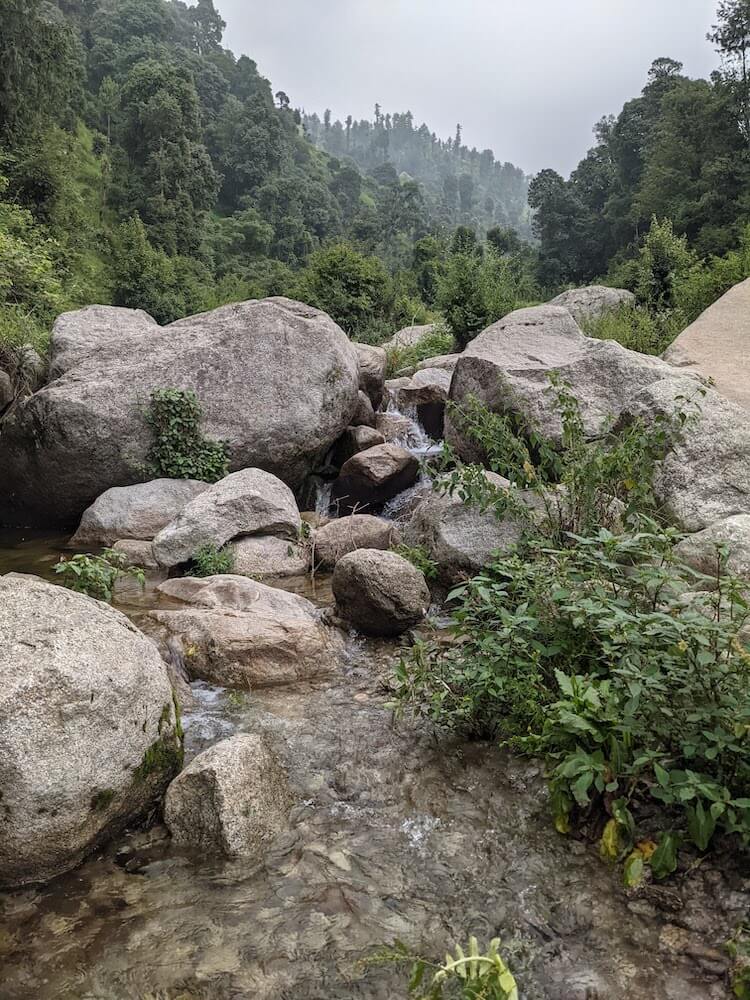

The brook flowed from right under the road but it had been falling from a wide open valley. We descended onto the boulders jutting out of the stream, sat on a big one, and listened to the water rush against them. Someone had, of course, washed their radishes there too as informed us the discarded yellow-green spiky leaves. After looking intently for lingudi: the local fern that grows in the water, we returned to the road.

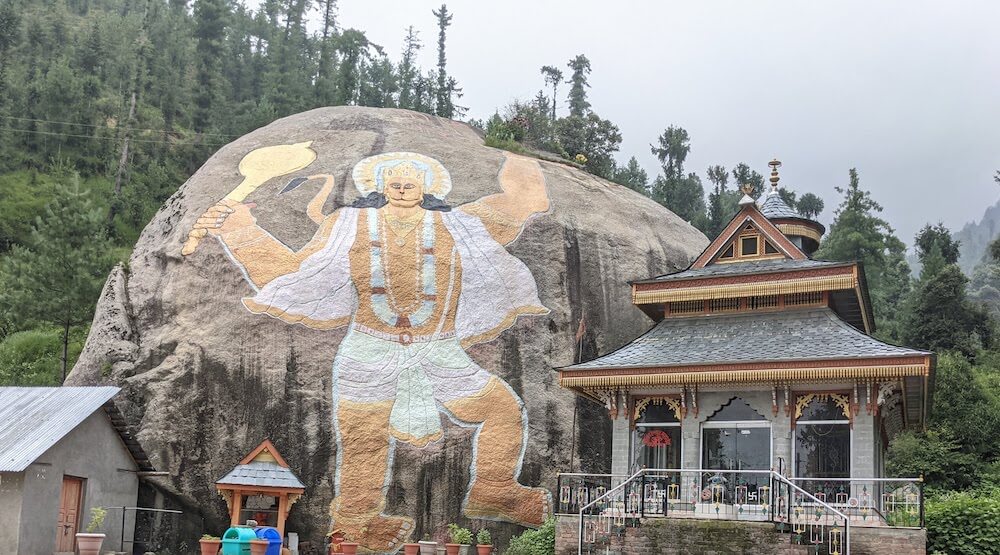

People were watching us, but at some point, we should stop caring. We reached the temple which had a monolith beside it on which Hanuman was painted. Fresh Himalayan water flowed out of a plastic pipe outside the shrine, and we drank our bellies full and filled our bottles from it. If you see a little stream falling off the Himalayan slopes consider it pure. Locals don’t dirty them (and neither they let anyone else) for they consider them holy.

Further the road was devoid of homes and the traffic was reduced even further to pick-up trucks, delivery vehicles, and a few local cars. The sun was hidden behind the clouds and the grey monsoon clouds were backdropping our adventure romantic. The river was left behind us but its coolness had spread to the trees.

We sat on the concrete barricades fringing the highway. Car drivers and passengers would gaze at us from their seats. But before we knew, they were already gone. At times, a shepherd returned home with his sheep. Or threatened by the greying clouds, a lone walker strode on to her destination. In such privacy, the saunter became even more pleasant.

At a junction, the road forked. And after a quick investigation of the hotels and homestays on the right side, we returned to the circle and walked ahead towards a trail meandering into the jungle.

We weren’t looking for a forest track to explore it. But the small bottle of local cherry wine we bought in the afternoon had been encouraging us to find a spot. The path we walked upon was fringed on one side by a wire that was fencing the dense jungle below. Charred wood and empty alcohol bottles indicated that many others used that grass patch to sit and drink. But that is the story of all green solitudes in Himachal.

We finished the wine bottle, made plans for our upcoming birthdays, and soothed the leg that had started to ache. But in the pictures from that afternoon, both of us tucked in the velvety green grass look too joyful and relaxed and invigorated to hint at any pain or discomfort.

Back at our homestay, our host received our radishes and said he would get their parathas made for us. We also asked for cottage cheese scramble, more stuffed parathas, curd, and butter.

It had been decided that we will breast the Kamru Nag peak the next day. But for then, we slept like babies who were exhausted after a day of thoughtless fun and frolic.

Feeling exhilarated as if I had been on the top of a mountain, that day I learned that we don’t always have to make it to the destination as quickly as possible, irrespective of how much others insist us or even if they rush to the top. Sometimes it is enough, and perhaps the right choice, to meander around.

People might stare. They might think us insane. We would find a few untrusting but some kind humans too. Even if no one would be pleasant, we could relish the simple pleasures of life: the deliciousness of nature, the surprises of the path, and the crispness of the bread that would fill us on that fortunate day.

Who knows what else we might find? Then sooner or later, we would reach the objective too. And when we would stand up at the crest, we wouldn’t think what lies beyond and what lay below our feet. For we would still have the bitter crunch of the fresh radish in our mouth and the ceaseless breaking of the river onto the rocks in our ears.

And oh, those cottage cheese fritters were too good with the wine. Good thing we saved a bit for later.

Our Homestay in Rohanda Village

Hotels and homestays in Mandi region can be found here.

Do you let go of a plan to just be?

*****

My much-awaited travel memoir

Journeys Beyond and Within…

is here!

In my usual self-deprecating, vivid narrative style (that you love so much, ahem), I have put out my most unusual and challenging adventures. Embarrassingly honest, witty, and introspective, the book will entertain you if not also inspire you to travel, rediscover home, and leap over the boundaries.

Grab your copy now!

Ebook, paperback, and hardcase available on Amazon worldwide. Make some ice tea and get reading 🙂

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter "Looking Inwards"!