On Being a Family

When my partner and I drove to Pondicherry city to stay for a few months, first, we booked a small Airbnb for three days. Though my experience with Airbnb has been poor, we reserved the one-room living and bedroom as no other accommodation on the various booking websites looked good or well-priced. The well-reviewed family guesthouse didn’t have even one poor feedback. Everyone spoke highly of the place and the host family. (You can read more on finding guesthouses in India in the link.)

The house was in the congested neighborhood of Tsunami Quarters—a housing colony made for fishermen whose homes were too near the coast. Tsunami Quarters was occupied after cyclone Thane hit the state of Tamil Nadu and Pondicherry on the east coast of India in 2011.

The Airbnb, just a ten-minute walk from the sea, was definitely in a fishing village, as we could tell by the heaps of fish drying on the streets. But as we arrived late, we couldn’t make anything of the neighbourhood until the next day. It had already gotten dark. The host came to pick us up with his little daughter and told us we would have to park on that main road itself. Without helping us with the parking any which way, he strode away.

Trailing behind, my partner and I were awkward. Our past experiences with Airbnb (and some Indian home stays) weighed heavy on our hopes and doubts. But with our two backpacks and laptop bags, we strode, too. The house was in a narrow lane of which one side was occupied by parked bikes and scooters. People were out and about.

The lady of the house, Shri, welcomed us and showed us the guest room behind their main house. Our space was a small bedroom-cum-living with an attached bathroom. The back door opened up to a tiny little garden. One couldn’t walk in it but could stare at it.

My partner and I gleamed with relief. The house was clean. The bathroom had toilet paper. There was a small slab for the kitchenette but it was not equipped (and also not mentioned as functional). I asked Shri if I could use the induction in the open cabinet underneath the slab. She hesitated to say that I could, but it belonged to a long-term guest who had kept it there.

We didn’t have to cook that night because we had eaten dinner on the way. Soon we snuggled into bed. The bedroom was quiet, and we closed its door to the outside world.

I woke up from the sunlight streaming in through the bedroom window. And from then until we left two days later, I got to know the family and spent a lot of time with them.

At breakfast, which was included, host’s two little girls brought us spoons, tea, and hot cases full of upma or idly. If we asked for more coconut chutney or sugar, they ran to their mother and brought us whatever we needed.

During the day, I wrote. The wooden chairs — which Shri told me were made by her husband — weren’t that comfortable. But she mentioned that she knew the seats weren’t the best and would have to be done something about. The little girls were my translators, but the mother also understood a little English and Hindi, and I caught a few words of Tamil. Years in Karnataka and my Tamil friends have acquainted me with its basic words.

Later in the afternoon, I remembered that we had a pile of laundry accumulated over our long drive from my parent’s home in Uttar Pradesh through Mumbai and Bangalore finally to Pondicherry. The washing machine was right outside their main house, and I threw all the dirty clothes in. (My most-loved and personally-stayed-in guesthouses in Bangalore are in the link.)

When the machine beeped its finishing music, Shri was already taking out the clothes. “Please let me do it.” I said. But it was hard to move her and get the clothes in the bucket. When I climbed to the terrace to put them up in the sun, she left her fish and knife to help me. I had to pull the wet clothes out of her hands as she clucked over me. Imagine the horror of making a kind woman hang our laundry as if we couldn’t do it ourselves. By that time, my partner had climbed up, too.

As Shri returned to her little wooden stool and continued the cleaning of the fish, we relaxed. A cat trotted in from somewhere and perched on the floor next to her, intently watching the fish she discarded in one pile or heaped in a steel bowl. Shri used the cutting tool with which my mother and her helpers cut greens and raw mangoes to pickle when I was a little girl (and even until later). A sharp C-shaped knife blade is attached to a wooden board which my mother held under her foot while chopping the greens against the blade. Shri scaled and gutted the tiny silver fish with such a natural rhythm that I couldn’t help but stare at her.

I confessed to the women that their place was clean and nice. And while throwing some scrapes to the cat, Shri told me that the father of the girls, that is her husband, and she cleaned themselves. The girls and their mother laughed about how the father pointed out things to say “that is still dirty” or “clean this” and so on.

The two sisters—one teenager and another much younger—were gamboling about their mother watching me shyly. If not the older, the younger was in that age when you are the axis of the world on which it revolves and every person exists to pleasure, entertain, and pamper you only. I leaned against the terrace railing next to the elder one, and when I asked, she told me the Tamil names of all the plants in the adjoining garden. I can never forget what is drumstick, coconut, and greens in Tamil because the girls gave me free personal lessons. My young teachers said cat was “Poonai” and that their mother and father were amma and appa. Then they repeated the Tamil words, and only when the elder one was satisfied, she said I had said all words correctly.

That day we ate out at a little home-run seafood cafe, got our second covid vaccination, and returned to find ourselves feverish and sleepy. As I awoke from a nap, laughter poured in from the courtyard. Listening to the family just be with each other, I longed to be with them, to steal some family time from their lives into mine.

As two young ambitious workers, my partner and I are mostly at something. When we are not, we relax, eat, and go around. But since we had just returned from the Himalayas after months and had some bittersweet memories from our family homes where we stayed for weeks, we were feeling the blues a little. The long drive from Himachal to Uttar Pradesh, then to Mumbai to be at his home, and via Bangalore, where we stopped for a day, had tired us out.

When I went to the courtyard, the girls, their father, and a couple of neighbours were all sitting on stone steps and watching a little pink chick scamper about. Astonished at its pink hues, I was told that the original owner (the human, not the hen) had colored the chick to embellish it and make it more saleable. But now it belonged to the little girl who ran behind it, letting it climb onto her and lovingly squeezing her so tight between her palms I wondered if it would be found flattened when she opened them up.

Showing the shells her little sister collected from the beach, the elder said, “She only picks up the rare ones.” “Do you go to the beach often?” I imagined them running on the sand laughing and jumping and eating ice cream. But they said they rarely went to the sea even though it was so close. The elders who were their chaperones must be busy cooking, taking care of the grandparents who visited often, and in carpentry, the profession of the father. After all, one has to keep it all going.

The youngest had her songs to which she liked to dance (I had mine once too) and they were played on my request. She took to the floor with the chick running hither and thither. Soon I was dancing along, laughing at her tricks. While the father and the rest of the family sat and clapped and watched us, it was more their daughter they admired.

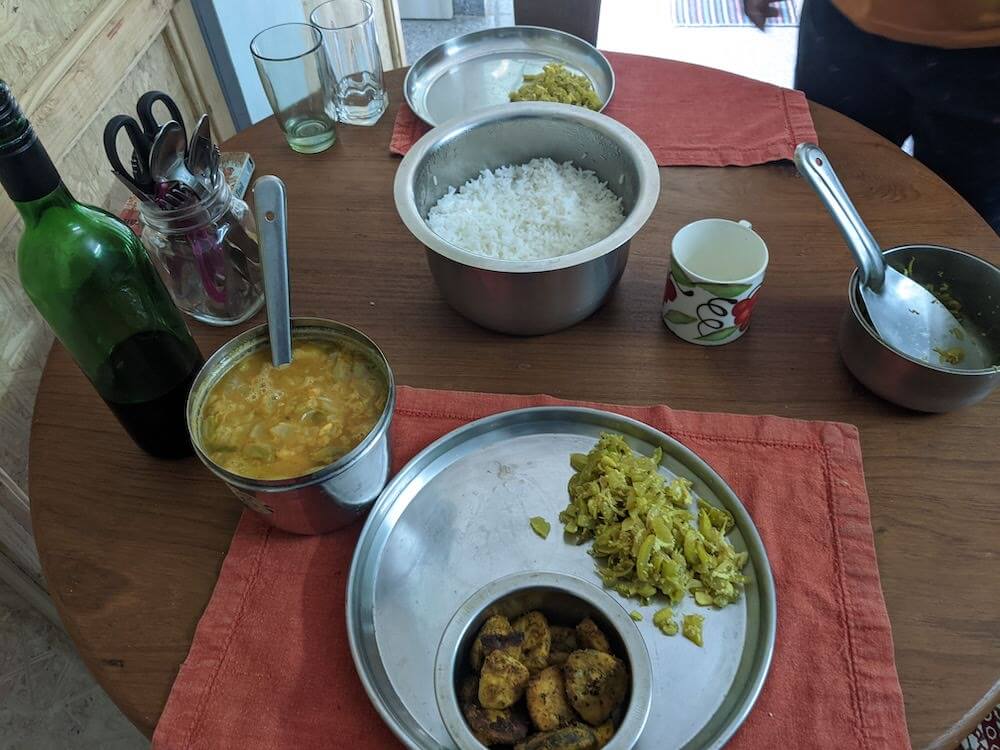

Listening to the rainfall over the tiled roofs and on the garden plants, we always went to bed early in that home. As the guest room was already booked for the rest of October, we couldn’t extend our stay. On our last day, we requested for lunch. After a couple of hours in which we reluctantly showered and packed and booked the next place—a hotel where we would be greeted by indifferent staff—the two sisters ran in with spoons and water as usual. We got dry cabbage stir fry (locally known as poriyal), sambhar curry, banana fry, and of course, rice as much as you want.

That delicious homely lunch was the best finale of our three days.

Apart from the simple homemade food that filled not only our stomachs but also our hearts, something else in that house satiated us, too.

Was it the quietness of the family that though watched television every evening while eating on the floor with their hands was never noisy? Or was it the absence of squabbles and screams and sharp stares one is used to hearing and being shared within families that soothed us? Or was it the playfulness and giggles of the girls, the chick, and the cat that rang on like a happy tune throughout the house suffusing everything inside and around it with joy?

The way the family members coordinated with each other imparted me a lesson or two on the true nature and benefits of the family unit. Not only love and load-bearing but respect, peace, and the most important thing—being happy in what they had—made the family a glowing independent cosmic of its own.

I understood why the father didn’t help us with parking that day. He didn’t drive a car so couldn’t tell us how to park it or how much space to leave. He strode away because he didn’t speak our language and we didn’t speak Tamil. It was not arrogance but his shyness in knowing that he couldn’t talk to us in English. So he rushed home where his daughters always jumped in to translate and he wouldn’t be awkward. When later the father sat quietly, laughing and watching his girls, never ordering anyone about, one could see how simple he was, doing his best at whatever he could.

Resentment or complaint felt foreign to that house as if they had never entered its perpetually open doors. It is not that difficulties did not fall upon it. But its residents seemed capable of stopping something discomforting or improper from turning ugly. They knew how to let go for the sake of peace. And so, within it, one could rest—as we did—and one could be.

As you should have people to draw energy from even if they are away physically, I have homes and families to take inspiration from, too. And that little fish-eating, chicken-cuddling Pondicherry home would remain one such infinite source of love and peace and the belief in their power. After all, everyone needs a window from which sunlight freely falls in and a cat forever lusting for fish can jump in.

Please note: I have changed names to keep the family anonymous and the feature photo is not of that home.

If you have loved this story, you would also love: what an old Himalayan woman taught me, My Chilean host mother’s bravery, methods to purposeful and happy living, what I have learned so far, and what the Little Prince thinks matters in life

Do you think that family has it all? Does anyone ever have it all?

*****

My much-awaited travel memoir

Journeys Beyond and Within…

is here!

In my usual self-deprecating, vivid narrative style (that you love so much, ahem), I have put out my most unusual and challenging adventures. Embarrassingly honest, witty, and introspective, the book will entertain you if not also inspire you to travel, rediscover home, and leap over the boundaries.

Grab your copy now!

Ebook, paperback, and hardcase available on Amazon worldwide. Make some ice tea and get reading 🙂

*****

*****

Want similar inspiration and ideas in your inbox? Subscribe to my free weekly newsletter "Looking Inwards"!

I thoroughly enjoyed this little family’s time in Pondicherry. The vivid descriptions of the places they visited and the life lessons they gained made me feel like I was there with them on their journey.

Hi Priyanka,

Enjoyed your story of Pondi. I had visited Aurobindo Ashram in 1970. Hope you checked out the same and Matri Mandir.

Nalin

I enjoy reading your posts Priyanka . God bless you .

Thank you 🙂

Loved this

Thx and keep it up

Glad you enjoyed it. Thanks for letting me know.